by Leslie Layton

2.3 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s how much – or how little, depending on your viewpoint – that the daily average temperature increased in recent years in the Paradise area.

That little temperature increase is what it took to create the environment for a deadly fire that would stun Butte County with its heat and swiftness, demolish almost 18,800 structures, kill 88 people and change the lives of almost every area resident.

Sure, there were other factors that contributed to the devastating character of what is now considered California’s deadliest fire. There was, for example, an increase in the number of sweltering days in recent years, reflecting our longer summers and shorter winters. Warmer nights, too, helped parch vegetation, making the Camp Fire unusually hot and explosive.

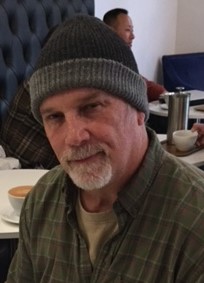

“Everything caught fire almost at once,” says Mark Stemen, a Chico State geographer. “The fire was burning so hot that it rained down on the whole area. This was a climate disaster.”

Climate change is sometimes mentioned as a factor in national media stories, but most people have a vague understanding – if they have any understanding at all – of how a climatic change that is barely perceptible worsens fire conditions. Understanding this, Stemen says, opens the door to becoming better prepared for the next fire and for work that can stem climate change, even at the community level.

Stemen says he’s been hearing from university colleagues across the country who live in fire-prone communities and are “just as scared.”

“All over California, we’re getting so much heat for longer periods of time that it’s drying out our vegetation,” he says. “This was a wake-up call for the entire West.”

But Stemen, who teaches sustainability courses and heads up Chico’s Sustainability Task Force, isn’t a man given to despair – even though he believes that climate change is transforming our world and we need to prepare for fires that are more destructive and frequent.

“It’s not the end of the world,” he says, “but it’s going to be a different world.”

The Camp Fire was extraordinary in both its heat and its speed, slipping like a storm cloud over canyons. It floated from a ridge in Concow to engulf neighborhoods and burn more than 153,000 acres. Evacuees have told reporters about melting steering wheels and shoes, and visitors to the decimated town have observed melted water tanks and motorcycles.

Butte County residents who walk, hike or spend time in their yards know how crunchy the leaves sounded beneath their shoes prior to this week’s rain, how dry the brush has looked. That’s because the vegetation is now storing heat instead of moisture.

Climate-forecasting models built by UC Berkeley’s Geospatial Innovation Facility and available to the public on the Cal-Adapt website show the 2.3-degree temperature increase that has taken place in the Paradise area. The models forecast warmer temperatures and more fire danger in the future. How grave the problem becomes depends on whether action is taken now to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

The website shows the average daily temperature in Paradise, between 1961 and 1990, at a little above 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Between 2006 and 2018 that daily average climbed to almost 73 degrees. Cal-Adapt forecasts a rise to only 74 degrees during 2019 through 2040 — if greenhouse gas emissions are reduced with action that would have to begin now.

Chico will go from having an historical average of four days a year with temperatures above 105 degrees to having 15 of those blistering days a year between 2019 and 2040 – but again, that’s a best-case scenario based on the premise that corrective action is taken to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Without action, there could be 17 days a year with temperatures soaring above 105 degrees.

In the near term, Stemen predicts, based on his study of the models, that Chico will have some searing days during the next few summers with temperatures ranging from 108 to 118 degrees.

“As my students say, ‘It’s gonna’ be hella’ hot,’” he says.

Stemen says Butte County communities will need cooling centers. Cities will need to plan development carefully and better prepare for major fires and other extreme-weather events. Chico could rely on solar and wind-powered electricity to cut carbon emissions.

The cost of inaction, Stemen argues, will be far higher than the costs associated with action.

Even given that the Cal-Adapt models predict more fire, drinking-water shortages, floods and scorching heat waves, Stemen is upbeat about what Butte County’s towns will accomplish. His optimism was renewed by the community response to the Camp Fire.

Even climate-change doubters recognize the Camp Fire was “something different,” Stemen notes. “A lot of people are saying, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this before.’”

“The generosity we’ve been seeing has just been beautiful,” Stemen says. “It has allowed us a brief vision into a world that could be. We’ve gotten the sense that there was something different. We had six hours of holy terror, and we’ve had 18 days of blessed goodness. That’s what we have to focus on – we have each other.”

The Enterprise-Record, in an editorial published Wednesday, writes about visits to Paradise earlier this week from Secretary of Interior Ryan Zinke and Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue. The Cabinet secretaries talked about the need to “thin the forests, rein in environmental litigation and bring logging back,” the E-R says.

Stemen points out that a 2008 Butte County fire burned through some of the same land as the Camp Fire. More brush-clearing and forest-thinning wouldn’t have stopped this forceful, low-lying fire.

The National Climate Assessment report produced by federal agencies that was released the Friday after Thanksgiving by the White House is an urgent call to action, too, by showing how climate disasters will affect the entire economy. “I don’t know that you can actually scream any louder in science,” Stemen says of the report.

Nevertheless, and particularly given the Trump administration’s position on climate change, Stemen says Americans shouldn’t expect solutions from the upper echelons of government.

“People can get really depressed if they look too high,” he says. “The real struggle right now is to imagine that new world, to not think that it’s all lost. It’s really incumbent on us because of our children. This is how we’re going to be stronger.”

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol.

right on Marc!

Thank you Leslie for your forceful article on the grave circumstances we face and the need to act now. Together we can change our behavior to put it in accord with the reality of human caused climate change.

Excellent synopsis of complex information. You rock, Leslie!