by Leslie Layton

posted Aug. 29

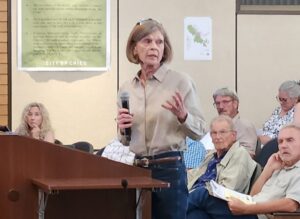

How to hold Pacific Gas & Electric Corp. accountable was a top concern at an Aug. 24 community meeting in Butte Creek Canyon following the canal failure that created a landslide earlier this month.

Butte Creek Canyon residents, still worried about the welfare of this year’s relatively small spring run of wild Chinook salmon, also want to know how future accidents can be prevented and whether steps to conserve the fragile ecosystem will be taken. The canal failure washed out a hillside, for a short time damming the creek and for a couple of days turning it sludgy orange.