by Natalie Hanson

posted Sept. 4

As racist and discriminatory speech become commonplace in electoral campaigns, candidates and campaign organizers are calling for a response. In Butte County and elsewhere, some would like elected officials to speak against discrimination and in favor of protecting marginalized Californians.

On a recent panel convened by Ethnic Media Services, organizers said that anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Republican Party is growing. Panelists said that many incumbents and GOP candidates use slurs against migrants, which fuels fear and anger against people who seek a better life in America.

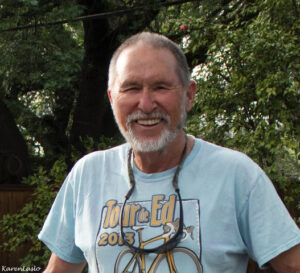

Hateful speech has been on the rise since 2016, said David Welch, secretary of the Butte County Democratic Party and chairperson for the Democratic Action Club of Chico. Welch said that “free floating anger” came to the surface with Donald Trump’s rise to power and the presidency.

Welch said that offensive speech has spread to local politics in Butte County, including both discriminatory language and “othering” directed at vulnerable groups like the homeless.

Rose Yee, who is running against incumbent Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale) for his District 1 congressional seat, said elected officials are tasked with challenging longstanding harm to their constituents.

“Only by naming harm can we start to undo it,” Yee said. “If elected officials care for everyone in our community — as they should — they are obligated to object when anyone in our community is subject to identity-based attacks.”

Anti-immigrant speech in the North State

Some elected officials say they continue to face anti-immigrant attitudes, despite their work to advocate for their constituents.

When Gridley City Councilmember Catalina Sanchez ran for office in 2020 alongside two other Latino candidates, ChicoSol reported on the discrimination the trio faced. For example, the Butte County Farm Bureau endorsed an ad telling voters to support “homegrown leadership” — a phrase that Sanchez said specifically targeted the immigrant community and implied that Latino candidates may not be citizens.

“I grew up here and I’m a citizen. Never did I think the bullying would be about race,” Sanchez said.

In addition, Sanchez said she found herself needing to be more assertive when first elected to the City Council as a woman and person of color in order to be taken seriously.

She said she finds it offensive to watch the region’s elected leadership call people “illegal” and advocate for “building the wall” in public statements. Their own communities benefit from employing migrants, she said.

“When local electeds speak to target border security and building a wall, they forget who they are talking about,” she said. “It’s their constituents they are talking negatively about. It’s also the undocumented immigrant community from Yuba City to the Oregon Border that is giving cheap, back-breaking labor to the ag industry with profits from the harvest of peaches, walnuts, grapes and rice in this region.”

LaMalfa has used the term “illegal immigrant” which Sanchez said is derogatory and singles out members of his district.

As president in 2019, Trump referred to other countries as “totally broken and crime infested places” and erroneously suggested that some progressive women members of Congress were from those countries.

Sanchez is running for re-election to the Gridley City Council.

Building the enemy

Manuel Ortiz Escámez, a sociologist and journalist who co-founded the news organization Peninsula 360 in Redwood City, said anti-immigrant language relies on the concept of “building the enemy.” The concept names the use of propaganda to vilify a group of people as a political tool to sow division and organize power around oppressing that group, he said.

Politicians know the power of words, and could speak out against propaganda, Ortiz added. He pointed out that racist speech toward immigrants, most notably from former President Donald Trump, has been successful in galvanizing support within some voter groups.

“Politics needs an enemy, because the enemy creates the feeling or urgency, creates unity, and the need of a savior, a hero,” Ortiz said. He pointed out periods in California’s history when anti-immigrant speech hurt communities such as Chinese workers, including some who lived and worked in Chico.

There are different ways to respond to hateful speech, according to Gustavo Gasca Gomez. An immigration outreach specialist with the Education and Leadership Foundation, he serves immigrants and first-generation children in Fresno, including those who need help with reporting hate crimes to authorities. As a former immigrant farmworker, he said discriminatory campaign speech can perpetuate stereotypes that are “demeaning” to him and his community.

As someone with a long background in campaign-watching in the North State, Welch agrees, stating: “Varying degrees of racism and bigotry against the newcomer have been a pervasive part of American history. So it’s really important that we acknowledge that to not deny that reality, and be willing to call attention to that.”

Welch said that successful candidates must call out hateful speech rather than “normalize it.”

For example, he said, City Councilmember Addison Winslow has spoken against language that many find demeaning of homeless people. Council candidate Mike Johnson has said he hopes to reduce the “othering” of homeless people through verbal and physical attacks.

Welch said that other elected officials ought to do the same, noting that candidates for office could partner with local organizations to show their support for marginalized people.

Natalie Hanson is a contributing editor to ChicoSol. This story was supported by an Ethnic Media Services Stop the Hate fellowship.

Excellent article.

“They’ve come to build a wall between us. Don’t let them win.” Crowded House