by Leslie Layton

posted Feb. 13

The recently-formed Tuscan Water District (TWD) is now in the budget planning stage after winning the right to levy a special assessment fee on landowners within district boundaries.

In an election held last month, TWD won the support it sought for a fee of up to $6.46/acre to be paid by landowners whose votes were weighted based on the number of acres owned. That was in accordance with California law that allows weighted voting in special districts, said TWD General Manager Tovey Giezentanner.

Giezentanner said the fee could raise up to about $620,000 a year that would pay for “general expenses, not around a specific project, but to fulfill the mission of the district.”

Giezentanner said TWD will “pursue service supply” and undertake both recharge and conservation projects to reduce groundwater overdraft. TWD must win approval for any new fees that would fund special projects.

Whether the election was the overwhelming win claimed by TWD is a matter of perspective. TWD critics say the voting mechanism – even though it’s allowed under state law – is undemocratic.

Groundwater for Butte, a local activist organization, points out that had it been one vote per ballot, the fee would not have won approval. Outgoing coordinator at Groundwater, Emily Alma, said the vote was 422 opposed to 404 in favor.

But each ballot was weighted by the number of acres owned by that voter and multiplied by what is the possible assessment fee. When votes were weighted by the number of acres owned, the fee passed with almost 88 percent approval.

If only the weighted vote is considered, “it looks like we, the opposition, were slaughtered,” Alma wrote in an email. Alma said “it took more than two weeks for us to get access to the ballots” to count them on a one person-one vote basis.

TWD held a Jan. 15 pulic hearing where landowners had a last chance to vote. The meeting, according to a report by North State Public Radio, was contentious, with some objecting to the weighted voting and others complaining that public notice was inadequate.

TWD debates

Durham attorney Jim McCabe, a TWD critic, told ChicoSol this week that he believes the election wasn’t conducted properly. McCabe was one of several people who worked successfully to stop a TWD formation vote in September 2022 because it didn’t meet state requirements for noticing and other issues.

“This is an effort to give large farmers — the largest farmers, really — a leg up in deciding how that water is exploited,” he said at the time.

McCabe argues that the fee is really a special tax that requires, under California’s Proposition 13, a two-thirds vote for approval.

Giezentanner responded to the special tax argument.

“There’s an argument out there for that,” Giezentanner said. “I don’t think it’s legally sound. You’ve got hundreds of special districts that are funded [this] way.”

Giezentanner described to ChicoSol the process TWD followed to hold the most recent election, noting that the district “hired a third party election consultant to handle the mechanics” who has conducted such elections in other special districts.

The weighted voting is a piece of the framework set up by the Legislature for special districts, he said, which can address irrigation, mosquito control, or in this case groundwater management. Landowners can say, ‘There’s an issue we want to deal with here,’” Giezentanner said. “In our case we want to bring more surface water into the area and reduce our use of groundwater.”

The certified election results show that 831 ballots out of the 2,057 that were sent out were returned. (Some 63 were returned as undeliverable.) That means so-called “turnout” was only slightly above 40% in a count of individual ballots returned. But Giezentanner says ballots returned represented about 60% of the district’s acreage.

The weighted voting matter has proved controversial and been used by TWD critics as an example of the problem inherent in forming the special district: It gives too much control over the aquifer, they say, to a small group of large landowners, not all of whom are locally-based.

TWD prepares to move forward

Giezentanner said TWD was thrilled with the special assessment election results, even though there were a few more ballots cast in opposition than in favor. From the start, he said, TWD expected that the “bigger parcels would get us over the goal line.”

The number of ballots returned -– and returned in favor of the fee — was a “big deal in an acreage-based landowner election,” he said. “We were thrilled with that. That’s a huge turnout to self-assess in a bad economy.”

The district was formed in 2024 in response to long-term worry over groundwater overdraft and a changing climate that increasingly delivers unusually wet and dry seasons in an alternating cycle.

In addition and more recently, Giezentanner said, walnut and almond prices have been down due to “oversupply, issues with transportation, all these other macro issues. We’re hoping we come out of it. It’s cyclical.”

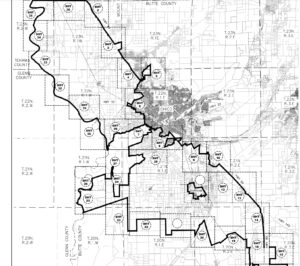

The district is comprised of between 96,000 and 97,000 acres, stretching from Butte’s northern border with Tehama County, west to the Sacramento River, east to Highway 99 and south to the Durham area. It bypasses most of the City of Chico.

TWD says it will work to reduce reliance on groundwater through conservation, by delivering more surface water and through recharge projects. Recharge involves the placement of water on the ground’s surface; the water is allowed to seep downward to replenish the aquifer.

In a natural process, water flows from the mountains to the valley, Giezentanner noted. “We want to slow it down to enhance the natural recharge process,” he said.

That worries environmentalists who say that recharge has troubling legal implications for water ownership. Environmentalists say that the replenishment that takes place in artificial recharge projects may not offset the groundwater pumping that was required, and the projects are often more detrimental than beneficial.

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol.