This story is second in a series on the Mental Health Diversion program and is supported by a USC fellowship.

Seven years ago, a 48-year-old Paradise area man was charged with misdemeanor assault with a vehicle. A medical report issued a few days after the incident stated that he was diagnosed with “bipolar disorder, mixed episode, with psychotic features.”

He was admitted and underwent a year-long treatment that included regular visits with a psychiatrist and a counselor, medication, and monthly court check-ins. After all the hard work, he graduated from the program, got his case dismissed and has had no run-ins with police since, he said.

Mental health needs have become a significant challenge in the criminal justice system, and the new county jail has been designed in part to expand capacity for treating inmates with mental illness. According to the Butte County Sheriff’s Office, on Sept. 30, 63% of 540 inmates were receiving mental health services and 16% were being treated with psychotropic medications.

But limited funding—along with differing views of the 6-year-old program—has hindered the expansion of the Mental Health Diversion (MHD) program that eases the burden on the jail. While stakeholders broadly agree the program can help people in need, the central dispute is over who is suitable to participate.

Scott Kennelly, director of Butte County Behavioral Health, told ChicoSol that the program is a lifeline for those at low points in their lives, and “jails are never the ideal place for people to get treatment.”

Kennelly believes the program should be expanded with services to help more participants succeed. To do that, it will need a lot more funding and resources.

People on Mental Health Diversion follow a treatment plan approved by the court through Behavioral Health or private providers, and monthly court check-ins are designed to ensure they are meeting all requirements.

Some defense attorneys, too, say the program helps deliver needed services, and believe that it not only reduces demands on jails, but also offers a pathway to a safer community. Those attorneys want to see the program expand.

But the District Attorney’s Office argues that defendants who have committed serious or violent crimes become eligible too easily, creating public safety concerns.

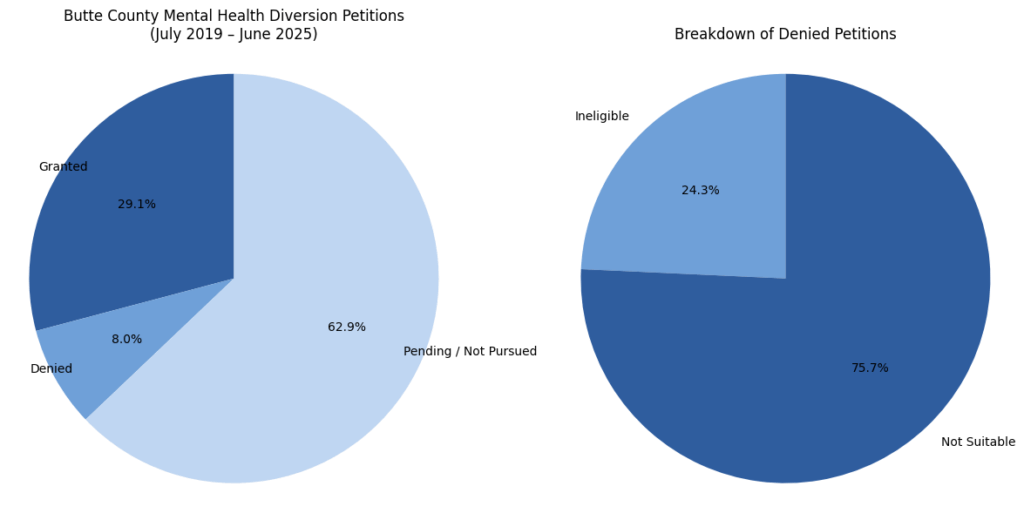

From July 2019 through June 2025, only about 29% of petitions filed by defendants seeking MHD were granted in Butte County, according to data from the California Judicial Council.

In rural Northern California, participation in mental health diversion programs varies significantly. Lake County has only one-third the population of Butte County, yet between July 2019 and December 2024, it had 330 granted petitions – a number comparable to Butte County’s 344.

However, in Yolo County, which has a population similar to Butte, there were only 14 approved petitions during the same period.

“I think if the state really wants to see this take off, they have to have a dedicated funding stream” – Scott Kennelly

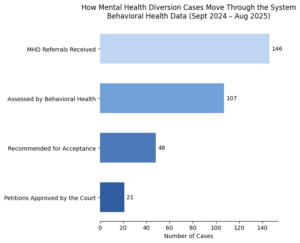

Entry into the program follows a tiered funnel: between September 2024 and August 2025, Behavioral Health assessed 73% of referred petitions, recommending fewer than half to the court. And of those recommended, more than 50% were denied diversion entry, data from Behavioral Health shows. That was often after the DA opposed petitions in a court hearing, the agency says.

More funding needed to expand the program

The program, which provides participants with treatment instead of jail time, is “incredibly effective for some people who’ve hit rock bottom,” Kennelly said.

The main challenge in expanding the program, he added, has been a lack of consistent and adequate funding for the positions for all service providers, including a robust treatment team.

“I think if the state really wants to see this take off, they have to have a dedicated funding stream that is sufficient to keep teams whole, and provide resources for housing and for vocational services and all the things that make people potentially successful,” Kennelly said.

Since the program’s launch in 2019, staffing shortages have constrained its growth. In the past, Ashley Starr, clinical supervisor of the MHD program, was the sole clinician responsible for assessing diversion petitioners, and it sometimes took a couple months for her to find the time slot to meet with a client and complete an evaluation.

Over the past six months, the team has hired three additional clinicians and two behavioral health counselors for the diversion program with county support, Kennelly said.

DA: Victims marginalized, program overused

Rather than favoring an expansion of the program, Mark Murphy, deputy district attorney who has been involved with diversion court since its inception, said legislation governing the program should be revised. Murphy, who said he has “mixed feelings” about MHD, has two main concerns.

“The law is written in a very broad way so that getting in is perhaps a little too easy for some people who may not have significant [mental] problems,” he said.

“And the law is written in such a way that the court doesn’t have a tremendous amount of discretion to decide who’s appropriate for Mental Health Diversion,” Murphy added.

A 2023 legislative change has made admission to the program easier. Murphy, however, said it has contributed to the program’s overuse.

“It’s overused in the sense that there are definitely people who have been charged with serious or violent crimes, and I have real concerns about them being in this program,” Murphy said.

Murphy’s second concern is what he says is lack of close supervision of Mental Health Diversion participants. That lack of supervision, in his view, just adds to the public safety concerns.

He suggests that the program should increase supervision of individuals “who have committed, particularly, crimes of violence, or may have significant substance abuse issues.”

Murphy gave other reasons for his opposition to some petitioners: If a person has had extensive mental health treatment in the past without making changes; if the treatment plan seems inadequate; or if the defendant hasn’t been honest about the offense.

In addition, Murphy’s boss, District Attorney Michael Ramsey, said victims may feel “marginalized” by the Mental Health Diversion program.

Ramsey explained that, under normal circumstances, victims can pursue restitution or a civil judgment if the offender is convicted. However, if the individual completes Mental Health Diversion and avoids a conviction, the victim may be unable to recover restitution.

During an interview with this reporter, Ramsey opened the 1.5- inch thick Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a book used by mental health providers that covers more than 200 disorders. He referred to it as a “cookbook,” saying that only a few diagnoses in the book were excluded from Mental Health Diversion.

“It’s easy for some folks to fake disorders to avoid responsibility,” Ramsey said. “I have problems with eye movement, then I have a mental health illness?”

For people who pose a danger to the community and need mental health services, the treatment should happen within the jail or under probation or probation-like supervision, Ramsey added.

Noting that there has been “an explosion of mental health issues over the years,” Ramsey said there is in-house treatment for jail inmates, but admits that more capacity is needed.

Some stakeholders – including Behavioral Health experts – believe that jails are not an appropriate place for mental health treatment, though.

“There are a number of things in jail that are not conducive to treatment,” Kennelly said. “Privacy, and there’s trauma, and there’s violence, and there are lots of things that impact someone’s stability. If someone’s able to get out of jail, get in a supportive environment, and have some kind of support network and go to some housing, they have a much better outcome than trying to get services in jail.

“In Mental Health Diversion, you have a team following that person with that person’s best interest in mind, and they’re not in jail, they’re in the community.”

In court: Clincians’ recommendations meet DA objections

Between September 2024 and August 2025, Behavioral Health received 146 MHD referrals and assessed 107 of them. Of those 107, the department recommended 48 for acceptance into the program. However, ultimately, only 21 petitions were approved.

Starr, who has conducted MHD assessments since 2019, said Behavioral Health considers several factors while assessing clients, including whether sufficient protective factors like support from family exist for them to succeed.

However, even after Behavioral Health recommends a case, Starr said, a petition can still be denied in court, and it happens often because of what she says are objections from the district attorney. She said it can be frustrating to see cases she believes have strong potential rejected.

“I did feel like they would be a good candidate for treatment,” Starr said, giving an example. “I feel like they would benefit from treatment. They had protective factors. And I would spend hours assessing them, and I would get a full story.”

Starr said because attorneys and the judges are not mental health providers, sometimes they don’t fully understand certain syndromes or a crisis event, and they may misunderstand the defendant’s progress.

In a Public Records Act request, ChicoSol asked to see MHD petition letters over a three-month period and the DA’s court filings related to those petitions, including any statements of agreement or opposition. In response, the DA’s office said extracting that data would cost hundreds of dollars, a cost this newspaper would be required to bear.

The DA’s office said it doesn’t track case outcomes, nor does it track the DA’s objections as a “data point.” Objections are sometimes made verbally in court without written filings, noted only on docket sheets that it says aren’t covered by the public records umbrella.

The defense: Those left behind should also be helped

Saul Henson, a local defense attorney who has seen Mental Health Diversion transform lives, including those of clients who may have been undiagnosed for a decade, believes that more people should be admitted to Mental Health Diversion.

Henson said he understands the MHD program is designed for people who can be stabilized and remain compliant, but he disagreed with excluding those “who don’t have all the ingredients to succeed.”

“Say you have a qualified mental health diagnosis, but they find you not suitable because you’re just too out there, and you’re not going to be able to participate in the program, or you’re not going to take your medication, or you’re not going to follow through, then they’re not going to give you this opportunity,” Henson said.

During the interview, an unhoused man tapped on the window of Henson’s office. Henson said the man was his former client, who has battled with severe mental health problems for many years.

“He’s a person who [the court] would not let in the Mental Health Diversion,” Henson said. “He’s been in and out of prison and he is not going to agree to change his lifestyle much.

“That means that segment is just getting kind of left at the abyss,” he said. “Where do they go? What happens with them? I don’t agree with the idea that we cut off a segment that are more needy and have more acute symptoms, and say ‘Sorry, you either have jail or the 1368 process [to restore a defendant’s mental competency to stand trial], or good luck.’”

Henson believes those people could also be admitted to diversion, but with more social work support and court check-ins; however, he acknowledged the limitations of the resources that exist.

“Those are the resources that we have,” Henson noted. “In theory, the idea is that by having an effective Mental Health Diversion program, maybe we can come back and ask for more funds in the future to deal with that other segment of folks that were not suitable or have some other type of services for them.”

Viewed through “different lenses”

Starr said ongoing dialogue, education, and communication among the program’s stakeholders could help align them more closely around shared goals.

“The DA is looking at it from a public safety lens,” Kennelly said. “Ashley is looking at it from a clinical lens. And there will be times where she says, ‘I think this person needs a shot.’ And the DA is like, ‘Absolutely not.’ That’s part of that whole collaborative team where there’ll be some where we all agree on, some where we won’t.”

Murphy, on the other hand, believes that, rather than trying to reach a consensus among stakeholders, it is more practical to modify a broadly written law.

“There’s always going to be a difference of opinion,” Murphy said, adding that the DA should focus on not only the defendant, but also victims and the whole society.

Attorney Henson said he understands the role of a gatekeeper like Murphy in balancing public safety with the mental health needs of defendants, but believes more people should be given chances.

“I disagree with the reasons the DA [uses to] object sometimes, and I think that I don’t give up on people as easily. So I’m someone who’s always giving someone an extra chance,” Henson said.

“It does you no good to go to jail when you’re going to get out and have the same problem” — John

John, one of the first program graduates, recalled that he was experiencing a manic episode at the time of the 2018 incident.

“I ended up outside of my house somewhere, and I didn’t even know what I was doing. I thought I was in a dream,” John said in a telephone interview with ChicoSol.

“I’m glad I didn’t go further and nobody got hurt,” John continued, adding that participating in diversion enabled him to better understand his mental disorder and realize the importance of taking medication.

“The program helps people because it does you no good to go to jail when you’re going to get out and have the same problem,” John said. “So why not fix the problem with medication or whatever it takes to [address] whatever the problem is when mental health will help.”

Now, four years after his graduation, John lives a peaceful life with his greyhound dog. He continues to see a psychiatrist and take medication, visit his parents and friends, and fish on the Sacramento River.

Yucheng Tang is a California Local News fellow reporting for ChicoSol. This series was funded by the USC Annenberg Center of Health Journalism National Fellowship. In an upcoming story, Tang will look at MHD cases terminated before completion.