by Leslie Layton

It is 7 a.m. on a cold, grey day in early March at the border crossing that connects Tijuana, Mexico, with San Diego, Calif.

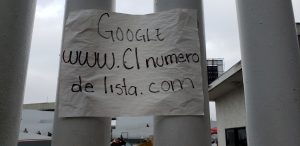

Some 25 migrants have gathered on the sidewalk below the port of entry. These are families on a waiting list, each with an assigned number in the 3,000 range. If any of their numbers are called today, they’ll get a turn to cross to the United States, and at some point — in what will probably be a very brief visit — a chance to make their case for asylum.

Newcomers are also arriving; one I notice immediately. She is a tall young woman with a toddler in tow who strides confidently toward us. She’s just arrived from Honduras, she says, slightly hunched from the weight of a framed backpack. She and her daughter are disheveled. Her large, dark eyes, tired. She is told to add her name to the wait list. Plan on a nine-month stay in Tijuana. Unwelcome news.

A shadow of despair crosses her face. Her journey from Honduras to this northern edge of Mexico has probably been harrowing; women who have made this trek alone give chilling accounts of the danger they faced, violence they suffered. Now she’s hearing that she’ll be stuck in Tijuana. She’ll need housing and work. She grabs the arm of her daughter and stalks silently away, disappearing onto a sidewalk crowded with beverage carts and food vendors.

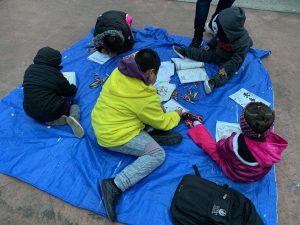

I’m part of a six-person group that traveled from Sacramento to volunteer for five days with Tijuana-based organizations assisting asylum-seekers. The Trump administration, with its “remain in Mexico” policy, has forced thousands of migrants to wait outside the United States as they pursue asylum cases. There are 10,000 migrants just in Tijuana, and I’m meeting a few of these resilient people during my stint with nonprofit Al Otro Lado (AOL) that runs a legal clinic.

This role, for me, is a new one. I spent 10 years working as a journalist in Mexico during the 1980s, so I saw what poverty and despair looked like then. I returned to Chico in 1992, traveling by car with a 2-year-old daughter who was as restless, needy and fragile as this little girl from Honduras. We crossed the Sonoran Desert in August without air conditioning, but my journey was a very different one. In comparison, it was a limousine ride.

I have never seen a border crisis like this one.

And now, of course, since returning to Chico and a world transformed by a pandemic, it’s far worse. Volunteer programs that delivered attorneys, translators, folks willing to be multi-tasking helpers – all suspended indefinitely. The Trump administration has taken steps to further shut down the asylum process, citing concern about the spread of COVID-19. This particular loss — one of many during the pandemic – feels ominous, sorrowful, as I spend my own days quarantined but comfortable.

During my week in Tijuana — the pandemic had not yet made its presence fully felt — day-to-day survival was an urgent matter for clients at AOL’s Border Rights Project. I’ve wondered what happened to the petite Haitian woman who showed up at the entrance, her black top fitting tightly over her swollen belly. She was pregnant with a baby due in four days.

I don’t know whether she and her companion had fled cholera, poverty or persecution, but there was little we could offer in terms of immediate asylum relief.

They were a 10-minute walk from San Diego, but we told them they could be stuck — for a very long time — in Tijuana if they pursue a case through the backed-up U.S. immigration courts.

I assisted a client who had fled to Tijuana nine months earlier. He had refused to transport drugs in his Mexican town, at which point traffickers threatened to kill his wife and two children. When he and his wife left the clinic, they had the court briefs they needed to pursue an asylum case. They still wore a look of grimness, but they cradled those documents with such care that I saw what the packet was — a thread of hope.

The truth is, sealed borders and towering walls are no match for nature in this inter-connected world. When I was in Tijuana, no coronavirus cases had yet been reported in the city, and there were few known cases elsewhere in the country. The number of reported COVID-19 cases in Mexico today? 848.

Daniel Turner-Lloveras, a UCLA professor and physician, warned earlier this week that leaving migrants in overcrowded living quarters on either side of the border is dangerous for them and for everyone else, too. During an Ethnic Media Services press conference, Turner-Lloveras, a public health researcher, said migrants who already have pending asylum cases should be allowed passage to the United States. Here they have family members or other contacts who can host them.

“If resources are being distributed only to a certain population… then by harming others we’re harming ourselves. In leaving others exposed, we’re really putting all communities at risk,” Turner-Lloveras said. “My belief is that you’re only as strong as the weakest link in a pandemic.”

The morning I spent at the Tijuana port of entry called Chaparral ended abruptly with an 8:14 a.m. announcement. The list keepers (they are also migrants) were told that no one would be allowed to cross that day to ask for asylum. The keepers had locked the gates to the Promised Land. The mood on the sidewalk turned morose; migrants who had been waiting since 6 a.m. gathered their belongings and returned to tent cities and crowded shelters and apartments.

Those who didn’t succumb to illness or financial crisis were back the next morning. The last number called at that port of entry was 3,852 on March 25.

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol.