by Leslie Layton

My childhood home is a pool of ashes contained by a cement foundation. The air in this once-Edenesque place smells almost acrid. The barn my father built from oak planks is a pile of rubble, with trickling aluminum melted into place on the ground.

At some point during the Nov. 8 Camp Fire that destroyed my hometown of Paradise, Calif., the white aluminum streams were trickling downhill as if headed toward the creek. No longer. There are almost no signs of movement on this still Sunday, Dec. 9. My former neighborhood feels like a cemetery.

I’m one of the fortunate in Butte County, unscathed in most ways by a fire that killed 86 people and displaced thousands. I haven’t lived in Paradise in many years, but for more than two decades, I’ve been within 12 miles of my childhood address that has names – Eden Road, for example — that have mythological dimensions.

Part of living at this address was living with a fear of fire. Every spring, we spent several weeks clearing brush and raking pine needles from around the house on the wooded ridge lot.

But we did not understand then what it was we feared, and I’m certain that the couple who bought the house 20 years ago didn’t know, either, what they should fear. None of us foresaw a fire that would float like a cloud and rain burning embers, leaving garden hoses and a sprinkler-timer intact, devouring or melting most of what was struck by those embers.

We failed to foresee that the climatic alterations underway would create a fire so swift that driven by high winds, it could move the distance of 80 football fields a minute. None of us foresaw what scientists call a “climate disaster” right in our neighborhood.

On TV news shows, reporters and anchors talk about how a changing climate created the conditions for California’s deadliest fire. But rarely have I heard them invert the words “changing climate” and say “climate change” – a phrase that would suggest that this is explicable, that humans have something to do with the fact that California’s fires are growing ever more deadly.

By coincidence, I visited my childhood home just a few weeks before the Camp Fire. The property owner had cleared out dead trees and brush and created a wide belt of so-called “defensible space.” She had done far more to protect the home from fire than we had ever done, and still she worried. This is how she’d evacuate if necessary, she said, explaining a plan for her and her dogs.

She promised to invite me for tea at this place we both considered sacred.

Those of us who lived in Paradise feared wildfire, but we presumed we had a good chance of saving both our lives and our homes — just as Americans assume they can survive hurricanes and tornadoes with preparation. We had fire hydrants and hoses at the ready, swimming pools and belts of cleared land, corps of rugged, skilled firefighters nearby.

Then came the Camp Fire like a mythic force, exploding in a parched forest, destroying most homes like a napalm bomb. The billions of dollars in insurance claims that will be processed do not fully measure what has been lost. The newspaper columns that described the town as “quaint” and “sleepy” do not capture the complexity of Paradise.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, when I was growing up, Paradise was an unincorporated community of mostly white, middle-class retirees and working-class families. For some residents, it was a refuge from what they viewed as an intrusive government. Town politics could be contentious and very conservative, and it wasn’t known as a welcoming place for people of color.

By the 1970s, liberal church groups were leading tolerance workshops and Paradise was struggling to adapt in a country transformed by the civil rights movement. Paradise itself underwent demographic change in recent decades, becoming a bedroom community for Chico and attracting artists, musicians and immigrant workers.

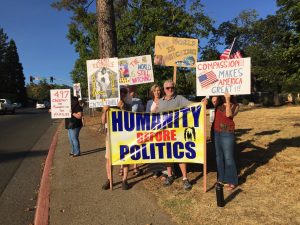

It still surprised me, though, when last summer a group of Paradise residents that included some of my former classmates held a weekly protest on the main thoroughfare, the Skyway — up to 80 people sometimes came — to oppose the Trump administration’s immigration policy and family separations at the border.

We had grown up in a town that lacked sidewalks or sewers, things you need government to do. But the freedom to roam, explore and imagine surely helped the town’s evolution.

Our winters were a series of storms that produced howling winds and beating rain, and our dry, warm summers perfect for lounging on rocks at swimming holes. I remember going to sleep on summer nights to the chirping of crickets. In the years since I’ve left Paradise, I’ve sought consolation in nature, places that are still and quiet, trees that are tall and sturdy, and I’ve noticed that my hometown friends share this connection to the natural world.

On this post-Camp Fire Sunday, as I wander through my former neighborhood, I feel like a visitor gazing at the remains of a civilization purged from the Garden of Eden. A China teapot peeks out from a pile of rubble. An empty lawn chair sits undisturbed by a house turned to ashes. A jacuzzi is a melted plastic rectangle.

I suddenly realize I have come to pay my respects: To mourn with the land, to grieve with the rumpled manzanita, to stare at 3 and 4-foot-diameter holes in the ground where for decades mighty oaks buried their roots until they were incinerated by the Camp Fire.

The towering pines that I’ve loved and that survived are brown and thirsty, and many with burned trunks and roots are being removed. Something new will grow in their place, but what that will be is open to question; California’s “Fourth Climate Change Assessment” report for the Sierra Nevada warns of a shifting “forest composition” underway as climate change raises temperatures, reduces snowpack and produces droughts and flooding.

Life continues in corners of Paradise and will renew itself in a revised form. PG&E employees work to restore power, acorn woodpeckers chirp from the bars of an empty clothesline and blades of meadow grass shoot up from a patch of earth.

There’s much to grieve now – lives lost, homes destroyed, a community dispersed. But if we forget to grieve the natural world we’ve already lost, we fail to grasp the entirety of this disaster and we’ll fail to change the shape of our footprint on this corner of Earth.

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol.

My friend, your agony is our agony. Your grief is our grief. I have fond memories of your hometown going back 30 years. The elegance of your words envelops my soul and shines a light of hope on the desperate scenario of our our Mother Earth. Blessings, Leslie.

Eloquent and moving. Thank you for including the natural world in our circle of loss.

Beautifully said, Leslie. You capture the delicate parts of this devastation that many of us don’t think of. I look forward to when I make my pilgrimage up the hill to pay my respects. Your observations will help me recognize the depth of loss. And I’m so sorry to all those whose homes and memories burned up – and to those who are mourning lost loved ones.

I agree with all the comments above: this a beautiful and touching tribute to Paradise. I also agree to a point you made in the article that we need more media reports – like this one – that aren’t afraid to use the phrase “climate change”and to help people make that connection.

Excellent and touching essay that captures this event that created such grief and is forcing a look at the future. Thanks and will share it .

We are working on a film and movement to connect this wildfire with the climate crisis. The project is called #ClimateUprising. We helped send a group of wildfire survivors from Paradise and community organizers from Chico to D.C. to attend Bernie Sanders National Town Hall on the Climate Crisis. Audrey Denney was part of the group that went, and we are planning to host a Town Hall on climate change in Butte County in spring of 2019. Please join us on Facebook and social media: http://www.facebook.com/ClimateUprising.

i think you will find this article interesting. it’s easily enough translated from portuguese to english. it’s titled, I will not be home for Christmas, and talks of the devastation of entire towns to a fire similar enough to Camp Fire, and the rebuilding that is not yet complete, the rebuilding being done entirely by volunteers and the short term long lasting effects of the fire on the lives of residents.

https://www.dn.pt/pais/interior/nao-estarei-em-casa-para-o-natal-10360664.html?utm_term=Pedrogao+Grande.+O+Natal+dos+sem-casa&utm_campaign=Editorial&utm_source=e-goi&utm_medium=email