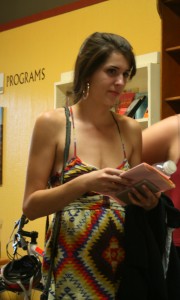

Madeline Hemphill demonstrates the grip that the students say officer Dyke used on Nicole Braham.

by Dave Waddell and Bianca Quilantan

What happened to Madeline Hemphill’s cell phone and the video she says would prove excessive force by Chico police?

It’s a question central to law enforcement investigations of the Aug. 27 arrests of Hemphill and her roommate and fellow Chico State student Nicole Braham.

A second cell phone video from the arrest scene — shot by Telvina Patino, a third roommate and Chico State student – has been viewed tens of thousands of times on YouTube and can be seen here.

Chico community activist Emily Alma has labeled the arrests an “excessive force event.” Also critical of police handling of the incident has been Michael Coyle, an associate professor of political science at Chico State. Coyle, who teaches criminal justice courses, said that if good policing means de-escalating situations, what’s shown in the video are poor police practices. “The video looks more like a basic training on how to escalate a situation, physically put someone in pain, and make them afraid of police,” said Coyle, who chairs the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) board in Chico. “Whatever happened to community policing?”

Beyond the question of excessive police force and some peculiarities surrounding Hemphill’s missing cell phone, the credibility of an Aug. 29 press statement issued by Police Chief Mike O’Brien also has come under scrutiny. Some wide discrepancies exist between law enforcement’s and the students’ versions of events – most significantly over how much time actually elapsed between their arrests and an earlier run-in with Chico officer Steve Dyke.

Hemphill, a 21-year-old senior psychology major, is certain the entire episode was rooted in retaliation for her filming of the police conducting a drunken driving investigation a short time earlier. While Patino’s video gone viral captures a good deal of Braham’s arrest, only a glimpse of Hemphill’s arrest is seen, though she can be heard pleading her case off camera.

Both Hemphill and Braham were arrested on suspicion of resisting arrest. Braham was charged with that offense by Butte County District Attorney Mike Ramsey, but Hemphill has not been charged and her case remains under investigation. Braham pleaded not guilty to the misdemeanor charge Thursday in Butte County Superior Court and is due back for a hearing Oct. 27. Hemphill and Braham each suffered minor injuries in being taken to the ground by police.

Chief O’Brien said a Chico PD internal affairs sergeant is looking into Hemphill’s claim that she was retaliated against for filming police at the DUI stop. Both Ramsey and O’Brien indicated that the use and whereabouts of Hemphill’s phone are key parts of their investigations.

Hemphill insists that immediately after officer Dyke ordered her taken to jail, she was “tackled” by other officers into a hedge of heavenly bamboo in the divider between the Esplanade and its eastside frontage road. Questioned about whether “tackled” was the proper word to describe what occurred, Hemphill said: “Absolutely. There’s no other word.”

Madeline Hemphill points to where she says she was “tackled.”

Hemphill said she clung to her cell phone, which recorded a bit of the Braham arrest and the beginning of her own arrest, until it was pulled from her hands by officers, she said. “The video shows them using excessive force on me,” Hemphill said. “I also think officer Dyke was trying to punish me for videotaping him.”

The last time Hemphill believes she saw her phone was shortly after her arrest while handcuffed in a police car. Several officers were gathered together; her impression was they were looking at video from her phone – while conversing and, at times, laughing. She equated the scene to that of a locker-room or break-room.

Chief O’Brien’s Aug. 29 statement claims that “Hemphill had lost her cellular phone during the arrest. Officers have searched for the phone at the scene, police station, and the patrol vehicle she was transported within. The phone has not been located.”

Hemphill insists she was asked by Chico officers twice – once at the scene of her arrest and again later at a Chico Police Department holding facility – for permission to access the video on her phone as evidence. Both times she said she granted them permission.

Although not mentioned in his press statement, O’Brien acknowledged recently that Hemphill was asked by officers “at least once to access her phone, but that was with the mistaken thought that we had possession.”

O’Brien at a recent meeting of the Police Community Advisory Board.

Braham, 19, was with Hemphill in that police holding facility. Unlike Hemphill, she had not been drinking the night of the arrests, acting as designated driver. Braham told the board of the Chico chapter of the ACLU, Northern California, at its Sept. 8 meeting, that she remembered a Chico officer’s exact words to Hemphill: “Is it OK if we use the video on the phone as evidence?”

Upon her release from the Butte County Jail, Hemphill’s cell phone was not among the personal property returned to her. It was a Saturday morning, the Chico Police Department was closed, but she was allowed into the lobby after buzzing in and pleading for her phone. An officer told her the phone was in evidence and the earliest she could get it back would be at her first court date. Hemphill’s father called Chico PD an hour or so later and also was told the phone was in evidence, she said.

Hemphill went home to sleep and awoke to find email messages about her phone. “I had gotten three emails in my sleep: change iCloud password, iCloud password successfully changed and Find My iPhone has been disabled,” she said.

Warrant Obtained for Missing iPhone

Hemphill returned to the Police Department on Monday, Aug. 29, and met with Sgt. Greg Keeney, who told her he didn’t know anything about her phone but would look into it. Keeney told her the email alerts she received about the phone’s use were consistent with police protocol for hacking a phone in evidence, according to Hemphill.

She said her father’s records also indicate her voice mail was called on Aug. 28.

Hemphill said use of her cell stopped Aug. 29, noting that was the same day O’Brien reported the phone was missing.

Hemphill was interviewed about the phone on Sept. 15 by investigators from the district attorney’s office. They told her a warrant was obtained to find out through Apple and T-Mobile where the phone was used during the three days after Hemphill’s arrest, she said.

“Apparently each time they open the phone up to use data there is a GPS in it,” she said. “They can go in and track it and see … where it was from.”

The Aug. 29 press statement issued by O’Brien makes note of Hemphill’s .141 blood alcohol content at the time of her arrest. What O’Brien’s press statement didn’t reveal is that police also tested Braham’s blood alcohol content at Chico PD’s holding facility. Braham’s test found no alcohol in her system, a fact not disclosed by police while trumpeting the drunkenness of Hemphill, who had not been driving.

O’Brien acknowledged that his statement excluded Braham’s .000 BAC but says he mentioned the fact in media interviews. Asked why Braham’s blood was tested for alcohol content, O’Brien said “BACs are often taken of arrestees to ensure proper prisoner processing.”

Hemphill contends that the police response to Dyke’s call for back-up while detaining Braham was one of the most sobering events of her life. Officers arrived to the scene quickly from seemingly every direction. The YouTube video captures Dyke, his knee on the prone Braham’s back, pointing to Hemphill and twice ordering her taken to jail — just as she was beginning to videotape the scene, she said.

“It was like we were living a nightmare,” Hemphill said.

O’Brien’s statement says that after Dyke ordered Hemphill’s arrest for “officer safety purposes,” Hemphill “tensed her arms in attempts to resist being placed into handcuffs. Based on her failure to cooperate and resisting arrest, Officers had to place Hemphill on the ground, where she was detained in handcuffs.”

Hemphill and Braham told the ACLU board that the attitude of the Chico officers toward them ranged from rudeness to ridicule – from the time they were arrested until they were dropped off at the county jail in Oroville hours later. “When we got to Butte County (jail), they changed us into these orange jumpsuits with chains around our waists before they cleaned our cuts, but it was the first time we were actually treated like human beings,” Hemphill said.

In Patino’s nine-minute YouTube video, Patino is at times heard talking with officers and frequently crying while filming. It was Patino’s car that Braham was driving that night. Patino, who had been out on a Friday night drinking with Hemphill, was the passenger. At one point Patino describes officer Dyke’s behavior to another officer as “super aggressive for no reason.” Later, when Patino is informed by Dyke that a burned-out license plate light precipitated the stop, she sounds incredulous. “Are you serious?” she asks him.

At another point, Patino questions Dyke about why he twisted Braham’s arm: “That was not OK,” she tells him. The officer responds that Braham refused to follow his order to get back into the car. “She (Braham) was sober,” Patino tells Dyke. “Her car was off when you pulled her over. …There are people drunk driving out there, and you’re going to get us for this? Like, we did everything right.”

Later in the video, Patino is alone and sobbing while calling out to Hemphill, who had disappeared into the night’s darkness and flashing lights: “Maddy, are you OK? Are you OK? …Are you OK, Maddy?” An officer approaches Patino and tells her that Hemphill and Braham are fine and headed to jail. “You’re just saying that like it’s funny,” Patino tells the officer.

Coyle, the professor and ACLU board chair, said O’Brien’s description of police treatment of Braham soft-pedaled the actual force used against her. As evidence, Coyle pointed to the following language from O’Brien’s statement: “… Officer Dyke made the decision to allow (Braham’s) own momentum to carry her to the ground.”

“The police chief’s description is an insult to anyone’s intelligence,” Coyle said.

Coyle: “…an insult to anyone’s intelligence.”

Hemphill said the claim in O’Brien’s press statement that Dyke had three times ordered her out of the street while filming the DUI stop was false, as was O’Brien’s suggestion in news accounts that she was trying to hide while filming.

DA Ramsey, in a Sept. 16 interview at the Butte County courthouse in Oroville, said that, unlike with Braham, there isn’t evidence to support a charge of resisting arrest against Hemphill.

Asked about Hemphill’s claim that she twice was asked by Chico police to access the video on her phone, Ramsey said Hemphill had “perception and memory problems” because she was intoxicated. Informed that the sober Braham claims she too heard police ask to use the video as evidence, Ramsey said his investigators had not been able to question Braham as a result of her retaining counsel.

According to Chief O’Brien’s Aug. 29 statement, Dyke noticed Hemphill filming the DUI investigation at 1:40 a.m. on Aug. 27 and that he pulled over the vehicle Braham was driving at 2:08 a.m.

Similarly, Ramsey said it was his impression that Hemphill’s initial filming of the DUI stop took place about 30 minutes before the arrests of Hemphill and Braham. But by Hemphill’s estimate, the time gap was actually five minutes or less – an account that, if true, might lend more credence to the retaliation claim.

Missing Video May Show Excessive Force

Hemphill said she feels a duty as a citizen to film police in order to curb abuses of power. That night, Dyke had been so angry about her filming, she decided not to get into the car driven by Braham, who had pulled over to wait. “I could tell by listening to him for one second that officer Dyke is an aggressive man,” Hemphill told the ACLU board.

O’Brien’s press statement says that Dyke had noticed in the initial encounter a burned-out license plate bulb on the car. Concerned about causing problems for Braham, Hemphill said she decided to walk the two remaining blocks to their residence in the 1000 block of the Esplanade. Braham told the ACLU board she, too, was surprised, sitting in the car, how much “that guy was really yelling.”

Nicole Braham prior to speaking at ACLU meeting.

According to Hemphill, after the DUI check yielded no arrest, Dyke headed north in his patrol car from the 800 block of the Esplanade and turned right onto First Avenue. It’s her supposition that he made three more immediate rights — onto Oleander Avenue, then East Sacramento Avenue, and finally onto the Esplanade frontage road. Dyke turned on his vehicle’s emergency lights as or after (depending on the account) Braham parked the vehicle with the burned out license plate bulb – “badly,” according to DA Ramsey – in front of the students’ residence. According to Hemphill, Dyke “ran” from his patrol cruiser to confront Braham as she was stepping out of the car.

O’Brien’s statement says Braham “failed to acknowledge three requests” by Dyke to get back into the car and also had to be told three times to drop her keys and lanyard.

Braham, who has not returned calls seeking comment, shortly after the incident told Chico State’s student newspaper that Dyke immediately yelled that she was being detained and to drop her things. “I took a step forward and he grabbed both of my arms, slammed them on (Patino’s) car, rag-dolled me around on the car and moved me to the police car,” The Orion quoted Braham as saying.

Braham told both the ACLU board and The Orion that she appears in the video to be pulling away from Dyke’s grip because he was bending her fingernail back while holding her hand and wrist, causing extreme pain. In The Orion account, Braham said it was Dyke’s twisting of her arm that forced her movements: “I couldn’t untwist my arm. He moved my body. I just took steps to not fall.”

As for Hemphill’s missing phone, Ramsey said there “doesn’t appear to be any advantage to the police of having that,” noting that Hemphill had filmed a DUI investigation in which the driver was cleared. Hemphill disagrees, contending her subsequent filming would prove that officers used excessive force in arresting her. “I capture that in my video,” she said.

Asked at the end of the Sept. 16 interview if he had any other thoughts about the incident, Ramsey paused, smiled and replied: “If they find that cellphone at the Chico Police Department, I’ll be really pissed.”

Dave Waddell is news director of ChicoSol. Contact him at DWaddell@csuchico.edu.

Thanks for giving this incident such complete and fair coverage. It is very important that this situation not be forgotten. It must be included in deeper exploration of how law enforcement in Chico operates. They claim to be acting within new and improved guidelines, leaning toward “community policing”, but in this situation it seems that police bullying is accepted practice, defended by the chief of police. This story is not over.

Thank you for putting a light in this situation, and fulling covering it. We need more coverage like this i think it can help everyone

Both Hemphill and Braham were arrested on suspicion of resisting arrest.

??? suspected of resisting? YOu mean they DID NOT KNOW IF THEY WERE ACTUALLY RESISTING ARREST? There was no evidence of resisting, but they SUSPECTED that they were, or were about to resist arrest?

Hey I support the IQ limit on police hiring, because if nothing else it keeps them too busy to steal school kids’ lunch money… but SERIOUSLY – WTF IS SUSPICION OF RESISTING ARREST????

Hi Joseph,

Thanks for the comment. You raise a good terminology point, but the “on suspicion of …” term was mine, not the police’s. It’s a term used, in part, to avoid saying “charged,” which is not something the police do. Charges are brought — or not, as in the case of Hemphill — by the district attorney. The “on suspicion of …” term can also be something of a reminder (to both the writer and the reader) that some people are not guilty of offenses they are “arrested for” by law enforcement.

My Reaction to the Officer Dyke Incident 9/25/16

As a citizen of Chico since 1972, when I came to town in my 20’s, then becoming a licensed contractor and local businessman for forty years, I am outraged by the excessive use of force demonstrated by Officer Dyke in the video. My experiences and stories I was hearing about Chico Police conduct in the ’70’s and ’80’s were good. Chico Police were known for giving more warnings than arrests. Fast forward to 2010. One of my customers is a former Chico Police Officer who volunteers a statement I will never forget, “Chico Police are the people Chico hires to beat people up.”

The video, referred to in the media, shows an angry, nearly out of control, Officer Dyke over reacting and being way too violent for what the circumstances justified. Officer Dyke appears to out weigh Ms. Braham by two to one. Judging from the video, Officer Dyke needs to be reprimanded, given more training, or fired. And if our Police Chief will not do that, then he needs to be fired. We have gotten to the point where citizens fear the police. That is wrong. Citizens finance the employment of the police, citizens are not the enemy.

This incident is made all the more concerning because of its backdrop: Kevin Moore’s harassment and arrest after he photographed the arrest of Freddy Gray; the harassment and arrest of Ramsey Orta after he photographed the police murder of, (“I can’t breathe”), Eric Garner; the arrest of Chris Leday after he uploaded the video of Alton Sterling being shot by police; and the arrest of Diamond Reynolds after releasing the video of the police shooting of Philando Castile.

“The First Amendment protects the right to photograph police. The people who are capturing police violence on video are the ones enhancing public safety here, as well as standing behind very well settled law.” (Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting 9/9/16)

We have to ask ourselves, do we want to live in a country of, for and by the people, or in a police state?

Are we to live our lives in a state of fear?