by Leslie Layton

There are many things to say about the Nov. 3 General Election, including this: in southern Butte County, the small town of Gridley has awoken from decades of political slumber.

Three incumbent city councilmembers were ousted in Gridley, and two of the candidates who won their seats are apparently the first Mexican-Americans elected to the Gridley City Council. This fact in itself is surprising, because about half of Gridley’s residents are identified as Hispanic or Latino, with the vast majority of that population coming from families that immigrated from Mexico.

“It’s high time that Gridley was represented for all citizens, not just a niche,” said Bill Bynum, a former Gridley resident who assisted with the campaigns of the two winning Mexican-American candidates, Catalina Sanchez and Ángel Calderón. “It was an interesting race.”

Three Mexican-American candidates – Sanchez, Calderón, and Jessica Ramos-McElroy, who placed fourth and therefore didn’t win a seat – campaigned on issues that for many in this low-income town, were urgent: COVID-19 safety, municipal power utility rates and jobs. They ran campaigns they describe as non-partisan, but all three are Democrats who were running in a town with a slight Republican majority and a reputation for conservatism.

The Gridley City Council race has proved instructive, suggesting lessons in how political campaigns that are community-based can succeed — even against considerable odds. Those lessons are under study in Chico, where Democrats are reeling from an election that demolished the liberal City Council majority. Four seats were lost to conservatives in districts where Democrats are a majority.

Bynum said the Gridley candidates did an “excellent job of articulating the issues” and “messaging” on social media. But also important was the “ground game” – the face-to-face contact. The candidates canvassed, hung fliers on doors and participated in forums, exploiting every opportunity for visibility.

“The lesson in Chico is that [liberals/progressives] need to get a ground game,” Bynum said. “They’re going to be outspent in every election.”

The Gridley race also foretells an increasingly competitive political climate in what was once a quiet Highway 99 farming town. Gridley — a town rocked by recent administrative scandal and a divisive political campaign – “is booming,” Bynum says. New development there has helped to ease the region’s housing shortage that worsened after the 2018 Camp Fire to the northeast.

Calderón, the third-highest vote-getter in the race for the trio of seats, has lived in Gridley for 25 years and said he has always felt welcome. But he was stunned by how antagonistic the race quickly became as opposition to a sitting Council emerged.

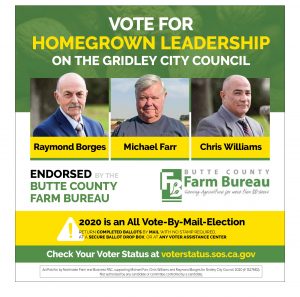

Some farming interests, Calderon said, worked to “separate the Mexicans who were running from the white people who were running.” Calderon points to ads that promoted a conservative slate that stated, “Vote for homegrown leadership …”.

“It’s OK when Mexicans work for them, but not OK when Mexicans run for office,” said Calderon, a counselor at Butte County Behavioral Health. “It was very offensive.”

Calderon said a couple of racist notes were left on his car; women involved in the campaigns said they were threatened with violence on social media. Ramos-McElroy said a community member directed a comment at her on social media, saying why didn’t she “get back to the kitchen,” while another didn’t settle for mere denigration and said she “needed her face kicked in.”

“I’m the same person you see in scrubs at the hospital,” said Ramos-McElroy, a medical assistant at Orchard Hospital. “All of a sudden I’m not welcome and I don’t belong? That kind of stuff really, really upset me.”

But in the day-to-day life of the town, where residents cross paths on the street, the trio sensed building excitement. “People were given hope,” said Sanchez, who won the second-highest number of votes and will serve as the first Latina on the Gridley Council. “There were a lot of young people in Gridley wanting civic engagement and this campaign allowed them to do that.”

The top vote-getter was rice farmer Michael Farr, who didn’t respond to a request for an interview. The new Council will be composed of Farr, Sanchez, Calderón, Mayor Bruce Johnson, and appointed Councilmember Zach Torres.

The Butte County Farm Bureau endorsed Farr and two incumbents up for re-election, Raymond Borges and Vice Mayor Chris Williams. Borges and Williams, who placed fifth and sixth respectively in votes, were thus ousted. Also ousted was Councilmember Quintin Crye, who won less than 5% of the vote.

ChicoSol contacted the Farm Bureau for comment, but it said its executive director was unavailable this week. The Farr-Borges-Williams slate also had the support of a political action committee, the Northstate Farm and Business PAC, that paid for publicity like the “homegrown leadership” ad that appeared in the Gridley Herald.

Calderon ran an inexpensive campaign with about $700 in contributions by walking neighborhoods and talking to residents. He worried about COVID-19 exposure, but half-jokingly says he has been on something akin to a “mission from God.”

Calderon has lost four friends in Gridley to COVID and knew there were residents in danger of losing cars or houses because they were out of work. He knew there had been a reluctance on the part of farmworkers to undergo testing at the height of last summer’s peach season.

“Somebody’s got to work to represent these people at the City Council,” Calderon said. “We’ve got to make sure residents are OK, are safe.”

ChicoSol reported in July that Gridley was responsible for a high number of the county’s positive COVID tests. Soon after, Calderon joined a committee put together by the Hispanic Resource Council of Northern California that began a bilingual prevention campaign, helping to stem the outbreak. Calderon would like to see agencies like Butte County Public Health devote more attention to Gridley, which he says is too often forgotten or viewed as a “satellite town.”

Candidate Ramos-McElroy was one of the positive COVID cases. Although she has since recovered, she became “incredibly sick” and has lung scarring from the virus.

Driven by her distressing experience, she pressed the city to comply with public health mandates. She approached city leaders on various occasions, asking that they wear masks in public and at Council meetings, but said she was met with disdain and dismissal.

Alarm in the community grew even more when the city-owned Gridley Electric Utility considered a large rate increase. The Council delayed action, but the utility shut off power to some households during the pandemic because of unpaid bills. Ramos-McElroy became a self-appointed advocate for a half dozen families who were scrambling to pay high re-connection fees. In one case a COVID patient was affected, and in another family, a quadriplegic lost access to essential equipment.

“[Gridley residents] are so afraid to confront the same people they have seen forever,” said Ramos-McElroy.

Still, it’s hard to grasp citizen outrage in Gridley without knowing the story of Paul Eckert, the city administrator and finance director who recently resigned. He had been hired to fill more than one position at a combined salary considered hefty in this valley town of 7,000 – in spite of what Bynum calls “red flags all over the place.” The abbreviated – and sanitized — version: Media reports say Eckert was arrested last month on suspicion of driving under the influence. (Update: The Butte County District Attorney’s Office said on Feb. 5, 2021, that no charge would be filed because Eckert had been affected by a prescription medication, not alcohol. Sources said Eckert has continued to work part time on contract with the city.)

One problem in Gridley, Bynum said, is that the city often waives developer fees and bears much of the cost of providing infrastructure for new development. Then, he says, it tries to “nickel and dime the people who can least afford it.” Mayor Johnson didn’t respond to a ChicoSol request for comment.

Sanchez, who grew up in Gridley and works as a lobbyist at a Sacramento firm that represents nonprofits, began considering a run for Council early last summer. She likes the fact that Gridley runs its own municipal utility, but was surprised “that our Council had even floated the idea of increasing fees at the beginning of a public health emergency.”

Lessons for Chico

How did a pair of Democratic candidates in Gridley succeed while those in Chico failed? Party leaders point to the obvious roadblocks liberals faced in Chico’s City Council race: In two districts, the vote was split between candidates on the left; hundreds of thousands of dollars were poured into conservative campaigns; city residents are distressed by homelessness, and in some cases, needle distribution.

Huge amounts of money were spent to “weaponize” those issues, said David Welch, chairperson of the Democratic Action Club of Chico. “The Council needed to take a much more urgent approach to the issues of shelter and a legally-sanctioned campground. If city government in general had taken a more proactive approach, there might have been a different outcome.”

Party leaders like Welch are also looking at what has been a slight shift in voter registration in the county from a Democratic to a Republican plurality – a plurality that seemed to grow in the weeks preceding the election. Some voters, they believe, were persuaded to register Republican by party activists circulating petitions to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom.

But there’s no escaping the fact that the campaigns run by Sanchez and Calderón bucked a national trend. The Democratic Party nationwide reined in door-to-door canvassing because of the pandemic. Locally, party leaders see the Gridley race as an example of the importance of voter contact through canvassing as well as other channels, like texts and phone calls.

They’ve also taken notice of young, emergent Mexican-American candidates and how communities of colors have re-shaped local races up and down California’s Central Valley.

Latinx voters exert influence in the state, the nation

Calderon, who began working in the fields in the Northern Sacramento Valley when he was 13, asked not to be lumped into a generic group like “Hispanic” or “Latinx” that includes diverse communities, a few of which support the Trump administration. Calderon belongs to a community that early on was the target of Trump insults.

“He [Trump] was very clear, very direct when he maligned the Mexican people,” Calderon said.

Latinx voters may be diverse in terms of culture and politics, but about 70 percent of them nationwide voted for President-elect Joe Biden. Voters under that umbrella will play a larger role in coming elections, said Justin Meyers, a member of the county Democratic Party’s Central Committee and the party’s statewide executive board.

“This is the older, whiter part of the state,” Meyers said. “We’re on the tail end of a statewide trend. It would behoove Democrats to make sure we engage [minority voters]. It’s incumbent on the party that everyone feels engaged.”

The Gridley City Council race, with door-knocking and issue-driven debate, was new for that town.

“When you have one party in control for decades, they run out of things to do,” said Calderon. “Even if something is really oppressive, they do it anyway. But when you question them, that’s when they fall down.”

Leslie Layton is a freelance journalist and editor of ChicoSol.

Fascinating piece and an important sign of how young children of immigrants from Latin America who often go far away to college return home to take leadership roles in their communities. We see this happening across valley California, from Imperial County through the smaller cities of Kern, Tulare, Fresno

and now northern California. it is changing the human face of politics in California.

These new elected officials are bringing bold new ideas to their cities.

so now it’s okay to judge people based on skin color, last name and ethnic identification? I thought we called that “racism”.