by Natalie Hanson

posted Aug. 1

Chico Unified School District is struggling to solve the staffing and fatigue problems plaguing schools across the nation — even with its coffers well-funded for the coming academic year.

Chico Unified Teachers Association President Kevin Moretti said teachers have been aided by smaller class sizes, block schedules at the high schools and more aides “when we can find them.”

However, new funding may not necessarily solve all staffing problems. Like many school districts across the country, Chico Unified has seen an increase in retirements and resignations during the pandemic. The district has raised the wages for lower-paid positions that are at a premium, like classroom aides and bus drivers.

“We have the money for it, just not the bodies,” Moretti said.

He said in a district with about 750 teachers, he considers it a lot if five people resign mid-year rather than waiting until the end of the academic year. “During the pandemic and last year, several weren’t willing to come back to the classroom and chose to resign,” he said. “We’ve had people say, ‘That’s it, I’m resigning.’”

Moretti said he thinks how teachers have been treated in an increasingly politicized environment -– and in particular attacks on how public education is handled — has had an impact on resignations and retirements.

Jim Hanlon, human resources assistant superintendent, doesn’t think there was a significant increase in retirements or resignations during the last year, but said there were more during the period from 2019 through the end of 2020. He said the total number of retirements reached only 28 during the 2021-2022 school year, and this spring is “not too different (from) any normal year.”

There were 51 resignations this year, compared to 93 resignations in 2020-2021. But 126 resignations were recorded in 2019-2020 -– most of which took place during the first year of the pandemic.

Hanlon did concede that overall, retirements are up since the pandemic’s onset.

“We have gotten a number of them because of COVID, but also because people are close to retiring anyway,” Hanlon said. “We’ve had chronic shortages of people from instructional aides to bus drivers to custodians. That’s where we’ve really felt the shortages.”

Chico Unified’s problems are not unique. Although Hanlon was not available for follow-up comments during July, across the nation schools have been scrambling to fill positions and keep classrooms staffed. The CUSD website showed a few unfilled teaching positions when this article was posted.

For many teachers, COVID was the tipping point, accompanied by a desire to be paid more and earn better benefits for a job that the publication EdSource describes as increasingly under fire from parents and politicians alike.

For his part, Moretti said he tends to hear only the worst stories from union members, and, “The people that are doing fine don’t call me.”

Moretti said for the past six years, the union and district have had “a really positive cooperative relationship, where we did not in the past,” which has helped improve communication about district hiring needs.

He said the school district worked hard to ensure opening schools during the pandemic was safe and to enforce protocols like masking, social distancing and cleanliness. This spring, cases were often in the single digits during a normal school week, which Moretti called a major achievement.

“It’s been a pretty stressful couple of years, but it feels like we’re getting back to normal,” Moretti told ChicoSol in an April telephone interview. “We feel like we’ve turned the corner here a bit.”

Children under stress, too

A major piece of the district’s funding will continue to be spent on children’s mental health needs and their overall well-being.

Chico Unified can continue to rely on about $16.6 million carried over from the $60 million emergency federal American Rescue Plan Act and Elementary Secondary School Emergency Relief funds, which all school districts received in 2020. The following total funds approved last year can continue to be used through 2024:

• Class size reduction K-12 -– $8.9 million

• Tutoring/Intervention -– $1.5 million

• 17 additional counselors -– $4.2 million

• Elementary and secondary summer academies -– $527,000

• Homeless/foster liaison -– $125,000

Assistant Superintendent of Educational Services Jay Marchant said in an interview in the spring that the board ensured that all full-time counselors would get a third year.

Counseling requests from students doubled in 2021-2022 from what they were in 2019

The district had only three part-time wellness counselors before the pandemic. But after hearing parents’ feedback in annual meetings — that counseling helped their children recover after the Camp Fire — counseling moved up on the ladder of priorities.

“We said counseling is our number one priority,” Marchant said. The meetings were part of the Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) process (see sidebar for more on LCAP) that takes place every year to identify areas where the district can use state funding to tackle learning obstacles and improve student test scores and educational outcomes.

Counseling requests from students doubled in 2021-2022 from what they were in 2019, Marchant added.

School board member Tom Lando said the district also focused federal pandemic relief funding on summer learning experiences, with improvements to facilities and materials to support those goals.

He said the district uses in-house benchmark assessments to ascertain academic performance gaps “given the unreliability of the state academic testing data during the pandemic.” Unfortunately, he said, they cannot use these funds on long-term investments like more staff in order to create lower class sizes with more small-group teaching.

“Gaps definitely exist, and both POC and low-income families have been identified as groups that are to receive additional support to increase academic outcomes, along with our homeless and foster students and our special education students,” Lando said.

“My personal pie-in-the-sky dream is that at least one of our elementary schools becomes a full-service community school, where almost all of a family’s lower-order needs — like food, clothing, counseling, etc. — are all baked into the yearly operating budget so that when a student shows up, they know they don’t have to worry about anything except learning.”

Despite the pandemic, the district’s leadership say it has maintained careful spending habits to reach this point. Superintendent Kelly Staley said CUSD has maintained healthy reserves, making it possible to use pandemic-related funding for new positions.

“We used the additional COVID-19 funds for much-needed services that directly supported our students,” Staley said in a spring email interview. “Chico Unified will be able to use the Educator Effectiveness Grant, which runs through the 2025-26 school year, to continue to fund most of the current counselors.”

Staley said the district prioritizes the identification of students who struggle to achieve educational goals, using surveys “to gauge their social-emotional wellness.”

“If a student either reports a need for support or is identified through the response analysis, the student is contacted by school support staff,” she said.

Funding to increase, but overall budget could shrink

Although staffing continues to concern officials, federal funding looks strong and the overall budget expenditures within the coming year are expected to hit $189.6 million.

However, the state cost-of-living adjustment has caused a drop in the overall projected budget through June 2023.

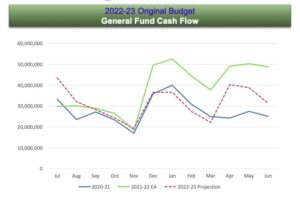

Chico Unified’s general fund ended June 30 with about $45 million. Based on the governor’s revised budget draft in May with a 6.56% cost-of-living adjustment, the next general fund is projected to end June 2023 with $40.7 million. The school district’s unrestricted funds – which can be used for anything – should hit $31.7 million this coming academic year, compared to about $37 million last year. Funds which have restricted, specific uses are estimated to reach $9 million compared to $8 million last year.

The board expects to have more state funding for the coming year, but must wait for the state Legislature to finalize Newsom’s new budget in August. Earlier this year, Newsom announced that the state plans to give schools and community colleges a whopping $128.3 billion and expand per-student spending to $22,850 as recovery from the pandemic continues.

The largest pieces school districts are waiting to hear about are an $8 billion one-time discretionary fund -– which schools can use to address mental health, professional development and pension costs -– and about $2 billion to combat declining enrollment and increase local control funding.

It remains to be seen how much from this funding each district will receive. Chico Unified’s Jaclyn Kruger, assistant superintendent for business services, said the budget presented June 22 and approved by the board June 29 is a draft that will be revised in August once the state budget is finalized. That means the budget in August should be larger than the draft the public saw in June, Kruger predicted.

Natalie Hanson is a Bay Area-based contributing writer to ChicoSol.