by Dave Waddell and Leslie Layton

Denise Minor had a dream that wouldn’t go away, a dream to teach Spanish at a university. And while it ultimately became a dream achieved at Chico State, it was first a dream deferred by the extreme challenges of mothering an autistic son.

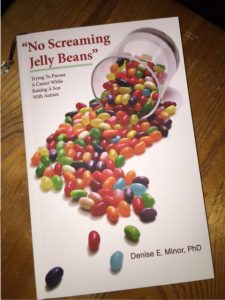

Minor, an associate professor in CSU, Chico’s department of international languages, literatures and cultures, chronicles her story in a new book, “No Screaming Jelly Beans: Trying to Pursue a Career While Raising a Son With Autism.”

Denise Minor and son Max

Minor’s new book includes essays published in different forms and at different times during son Max’s life. She believes she benefited from her work on “No Screaming Jelly Beans” — even beyond the therapeutic value that can come from writing narratives — after the notion of a book took hold in her mind.

In 1996, Minor and her husband Alex’s second son, Max, was born. Their first-born, Nathan, is three years older than Max. At the time, Minor had a master’s degree and a job she enjoyed teaching Spanish to health-care professionals at the University of California, San Francisco. But the twin desires of obtaining a doctorate degree to fulfill her dream, and for her sons to be raised in a safe community with good schools, turned her focus to UC Davis.

“I threw everything behind that one application,” Minor recalls.

Davis accepted her. She was 40 years old and “astounded at the people in class – very competitive, very smart people” whose competitiveness was actively stoked by their professors. She also taught classes to undergraduates. To complicate matters, she was up much of many nights because Max was a “terrible sleeper” due to breathing problems.

“I was teaching every day, taking these seminars and completely worn out,” Minor remembers. “I lived in a state of exhaustion.”

When Max was 2, Minor realized her son was delayed developmentally, including his language skills. “And he didn’t play,” Minor told ChicoSol in a recent interview about her book. “Two-year-olds play.”

As Max turned 3, Minor, a year into her doctoral program, dropped out of school in order to be part of a behavioral intervention program. She had enrolled her son in a home-based education program for autistic children that involved a tutor as well as a 30-hour-a-week commitment from Minor.

“This program became my full-time job for two years,” Minor said. “As soon as I knew Max was autistic, my ambitions took a back seat. There was just no question – the possibility that he would be able to function at a higher level was much more important than getting a Ph.D.”

The curriculum was based on achieving incremental progress in a child – from potty-training to properly greeting people to “being able to go to Farmer’s Market without being overwhelmed and throwing a tantrum,” she said.

Two years later, when Minor resumed her studies at UC Davis, she took only one class per quarter for the first year, giving her time to devour each professor’s proverbial “optional supplement readings” that few doctoral students have time for.

“Oh my god, I was so well prepared,” Minor said. “I felt how different that made me in the classroom community. … This time I was on the top.”

While excelling in both her studies and her teaching, the mothering part of Minor’s life included times of joy as well as times of extraordinary stress and uncertainty. And then came “The Crisis.”

Max (right) goofs off with a pal.

“When Max was 9, we had a crisis,” said Minor, who describes that period in a chapter titled “The Crisis.” Prior to that, Max had been relatively high functioning. “Slowly, he started doing really strange behavior … losing speech, becoming severely depressed.”

Minor stepped back again, dedicating herself full time to Max for the next year. Still, over a nine-year period she managed to complete a doctorate.

After finishing her dissertation in 2007, Minor applied for only one professorship, at Chico State, once again banking on a single application. She was hired that same year, and at CSUC would develop a specialty as a scholar is Spanish linguistics with an emphasis on second language acquisition.

For years afterward, however, she felt obligated to set aside her writing of “No Screaming Jelly Beans” to focus on more scholarly works that would allow her to gain promotion in academia. She previously co-wrote a book titled “On Being a Language Teacher.”

Minor said one of her projects now is to have Spanish declared the “co-official language of California,” which would ensure that it’s taught in most public schools. “Before puberty, children can soak in a language naturally with very little effort if the educators know what they are doing,” she said.

Also delaying completion of her book about Max was a horrendous battle with Stage 3 breast cancer that Minor fought in 2013 and 2014.

Given the seriousness of her diagnosis, Minor suffered through three major surgeries and then five months of chemotherapy, including one particularly powerful chemo session with what she described as “the red devil.” Then, at Stanford University, she endured six weeks of daily radiation treatment.

“They had to radiate everything a lot,” Minor said. “I was fried, absolutely fried. I looked like beef jerky.”

Today, Max is 21 and enrolled in an adult education program at Chico High School. He lives in a small residence next to his parents’ house. Minor’s husband Alex is an “amazing cook” who prepares soups and stews for his son when Max isn’t partaking in another of his favorites, a Zot’s hot dog.

Max Minor

Minor reads to Max nightly, and one of the books they’ve been reading, Mark Haddon’s “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time,” has a character that Max especially relates to — a character whose behaviors are controlled by rules inside his head.

“He’s like me,” Max wrote in an email to his mom.

“Max has many rules,” Minor said. “And one of them is that he can’t talk anymore.”

But he is communicative nonetheless and sometimes writes four emails to his mother in a week. Minor said his writing shows his “intelligence and sweetness.”

“He says nice things about the people who work with him and thanks me for taking him places,” Minor said on a recent Tuesday as she returned home from a trip with Max to the Chinese Temple in Oroville.

Minor found solace in fulfilling this other dream – the dream of writing a book about raising Max.

Minor said she’s seen many parents shelve their goals entirely to devote themselves to their autistic child. “I wanted to send a message to mothers in this situation,” she said. “Your family is more important than anything else, and sometimes you have to postpone the dream, but don’t give up on yourself.”

In one of the book’s last chapters, “Parting Words,” Minor emphasizes this point. “We can give and give and give, and it will never be enough,” she writes of autism. “What if we decide that we will hold back some of that energy just for ourselves?

“Yes – we will fight to get our children with autism the best services possible… But if we have a dream… we have to begin very soon. And what if this thing we want to create or this person we want to become is made better, is richer and has greater depth because of our struggle with autism?”

Dave Waddell is news director at ChicoSol. Leslie Layton is editor. Denise Minor was invited to join the ChicoSol Board of Advisors after this story was written, but in the interest of full disclosure, before its publication.