The Butte County Board of Supervisors voted 3-1 Tuesday to endorse the formation of a new, landowner-run water district in which members will get one vote per acre of land they own. Members may also have to pay a hefty fee to belong to the governing body that will have authority to implement projects affecting the region’s aquifer.

The proposed Tuscan Water District (TWD) was endorsed by board Chair Bill Connelly and supervisors Tod Kimmelshue and Doug Teeter after hearing more than two hours of impassioned testimony from dozens of members of the public. (District 2 Supervisor Debra Lucero cast the lone vote in opposition and District 3 Supervisor Tami Ritter left the meeting early because of a personal emergency.)

The Tuesday vote followed an earlier protest outside the county administration building by some 50 people who called the proposed TWD a water grab by powerful agricultural interests and a way of privatizing a public resource. The board had received hundreds of comments from citizens by email on an issue that only seemed to present itself recently.

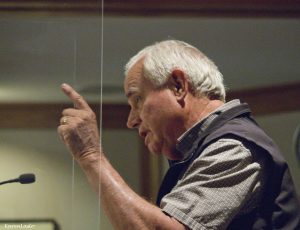

At stake is the health of the Tuscan aquifer system, which, says water analyst Jim Brobeck, is viewed by the state as an “under-utilized” water basin — even though it has been tapped aggressively during the past 10 years by deep wells.

“The Butte basin is probably going to hit historic lows” this year, said Brobeck, who serves as the environmental representative on the stakeholder advisory committee for the Vina Groundwater Sustainability Agency.

But the matter of the Tuscan Water District has apparently been in the works for years and now goes to LAFCo – the Butte Local Agency Formation Commission – which says its mission is to “promote orderly growth and development in Butte County …”.

Supervisor Lucero laid out her concerns about the hasty way in which the TWD came before the public — and calls it a “private, pay-to-play” concept — in a ChicoSol commentary here.

“I think Butte County has abdicated its role by making this recommendation,” Lucero said after the Sept. 28 meeting. “We should be watching out for everyone, not just wealthy corporations. This will clearly benefit the top 2 percent.”

But District 4 Supervisor Kimmelshue said the TWD presents an opportunity to improve the groundwater supply and increase surface water use, that he’d like to see groundwater “30 feet below the surface the way it was when I was a kid ….”

Kimmelshue said he wants to see the TWD bring Paradise water to the valley floor and he wants to “do something” about climate change. “I have great faith in the folks on LAFCo,” said Kimmelshue, who is himself one of seven LAFCo commissioners. “I ask you to trust your public servants and don’t believe in all these conspiracy theories out there.”

Lucero says TWD is unnecessary and other steps can be taken to meet the deficit for residents on shallow wells that have run dry. Chair Connelly rejected her suggestion Tuesday that there be a more critical presentation of TWD at the meeting, noting the huge number of cards that had been submitted for public comment.

Critics like Lucero argue that another layer of bureaucracy would be created at a cost of about $500,000 year. While TWD would not be a regulatory agency, it would have the power to tax and use eminent domain.

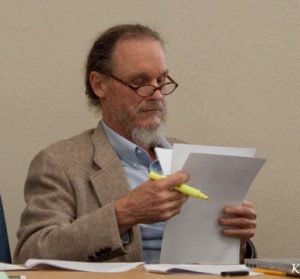

Durham attorney Jim McCabe spoke against the TWD Tuesday, and previously to a KZFR talk show, “The Real Issue.”

“Tuscan wants to get this through, because, frankly, they don’t want to have a lot of scrutiny,” he said. “This has been able to fly under the radar. But there’s no rush.”

Public may have little access to TWD

Many TWD opponents said Tuesday they’re alarmed by the undemocratic character of TWD, that it could take over aspects of groundwater management, creating a water oligarchy. Speaker Blake Ellis said it worries her that an agency is being created that will be “exempt from the Brown Act and public accountability.”

TWD’s website says that more than “70 local family farms and hundreds of landowner interests” have joined to form the TWD, and identifies proponents as “generational farmers and ranchers.”

Many of those “generational” farmers spoke at the meeting in favor of TWD, sometimes creating the appearance of tension between a deeply-rooted agricultural community and an increasingly urbanized county core. But other speakers suggested the divide was more complex — a sometimes partisan divide over how to preserve the character of what historically has been a water-rich community.

Lee Heringer from M&T Ranch said almonds and walnuts have been grown here for over a century and are the “backbone of this county.” His ranch, he noted, pays employees well, provides health insurance and donates generously to Chico State and Enloe Medical Center.

But while the water district’s formation has been propelled by some local farming families who want to conserve groundwater, the mix also includes land-owning corporations based out-of-county.

Many TWD critics – including small farmers, environmentalists, residents – said they aren’t anti-farmer. Chico’s Emily Alma said she’s a co-owner of a 12-acre farm in Kimmelshue’s district.

“We were never invited to join the Tuscan Water District and would not have been able to afford the entrance fee,” Alma said. “We would only have 12 votes. This whole thing just feels really twisted to me. I’m really concerned, Tod Kimmelshue, that you don’t have my interests at heart.”

Some members of the public said Kimmelshue should recuse himself from voting because of an alleged conflict of interest related to past campaign donations and his family’s land holdings.

A step toward privatization?

The TWD’s use of the word “recharge” in its filings has many critics worried. If the aquifer is re-charged with surface water — that’s water available at ground level in streams and lakes — the imported water would intermingle with groundwater already there — but be owned by the individual who supplied it.

“The complexity scares me,” said Richard Coon, who runs Chico’s 160-acre Wookey Ranch, in a telephone interview today. He wonders if the water owner would then be able to pull it out somewhere else and sell it to a water district that would then ship it south.

“Agribusiness in the San Joaquin [Valley] is really, really up against the wall; it’s like an arms race and that’s what worries me about this,” said Coon, who says that as a dry-land rancher he has no reason to belong to the TWD.

He indicated that while he doesn’t support the TWD, he’s sympathetic to the extent that some farmers are in an “overdraft situation and knew they were going to get told, ‘You have to rip out almond trees.’ They saw the writing on the wall.”

“Five years more of drought and we’re going to be collectively in trouble,” Coon added.

Jim Brobeck

Brobeck says Coon is right to worry because local ordinances or regulations designed to protect the area’s water supply and prevent sales to the thirsty San Joaquin Valley may be overrided by the state legislature.

Brobeck notes that the “recharge” concept promoted by TWD is also called “water banking,” and requires drawing down the aquifer so there will be new storage space.

The increased use of surface water suggests there are plans for the expansion of irrigation canals that will channel water from various creeks in an effort to refill aquifers.

Because there are no more rivers to dam, Brobeck said the movement statewide now is to “create underground storage.”

“First you have to evacuate a relatively-balanced aquifer,” he noted. Surface water is then moved and “spread on land in such a way that it will recharge the aquifer.”

If that were to happen, he has warned that Chico’s tree canopy — the big shade trees that lower temperatures — could suffer. “Urban forest relies on the shallow aquifer,” Brobeck recently told “The Real Issue.”

“Our mature trees have to be tapping the aquifer. If you pull down too far, the trees won’t survive, and this could change the environment in Chico drastically.”

“Five years more of drought and we’re going to be collectively in trouble” — rancher Richard Coon

What’s next

Kimmelshue said he doesn’t want water to be shipped south — he wants to see it used to “irrigate our crops.”

Brobeck agreed that many local farming families aren’t backing the TWD with the goal of selling their water out-of-county, but he notes that the “Tuscan Water District is very vague on what they want to do.”

“The big players,” he said, “have recognized that the California water market is rapidly developing and they don’t want to be left out.”

To prove his point, Brobeck sent several documents to ChicoSol. One, for example, was produced by the influential Public Policy Institute of California. In a policy brief published earlier this month, “Improving California’s Water Market,” the writers argue that local water district rules preventing water exports are “overly restrictive,” and Butte County is used as an example.

“In Butte County, for instance, it would take 18 months to go through all the steps to obtain a permit for a same-year groundwater substitution transfer,” the writers note.

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol.

Since Kimmelshue is a Supe, sits on the Vina GSA, also appointed the Chair there, as well as sits on BC LAFCo – received $80K for his campaign from this TWD group’s initiators and his brother is active in it, and they will be direct beneficiaries – how is that not a many sided conflict of interest?

Industrial BigAgs such as the Mormon Church and mega ag, aided by some smaller farms, want to pre-empt the state Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA)’s control in Jan 2022 – so that’s the reason for this big push rush to get the Supes to pass the TWD as quietly fast as they can.

I’ve learned from researching Stewart Resnick, the Beverly Hills billionaire who is the largest farm owner in CA, whose ever-expanding water-intensive food crops in SoCal: when your dynasty is in the desert, you get really good at stealing other peoples’ water. Resnick now privately owns the majority of the public water that flows south from here. TWD is right out of his playbook. Salt Lake City is in the desert, too, HQ of the Mormon Church which owns a huge industrial ag business called Deseret Farms.

Water Kleptocracy: One Acre, One Vote

Democracy: One Person, One Vote

Support local ground-water dependent farmers!