Zero. That’s the number of hate crimes that took place in Chico in 2018, according to reports to the FBI from the Chico Police Department and Chico State’s University Police Department.

That zero doesn’t reflect what happened to an African American man, who has said he was pelted with beer cans last year by several white people in a pickup truck who were using the N-word. He never reported the incident to police, but his girlfriend saw the bruises.

The zero also doesn’t reflect other unreported incidents, and it doesn’t reflect incidents that may have been driven by hate that didn’t surface in a police report or court hearing. And it certainly doesn’t reflect overt and subtle offenses that left people who were subjected to them feeling hurt and scared.

Hate crime statistics provided by local law enforcement agencies, for several reasons, don’t mirror the violence and bias that members of Butte County’s minority communities face. In dozens of interviews during the past three years — as a media partner in the nationwide “Documenting Hate” project — college students and community members have described an increasingly hostile social climate.

Chico police (CPD) reported to the FBI that there were four hate crimes in its jurisdiction during the three preceding years, 2016-2018. But police departments vary greatly in how they track hate crime, and the CPD figure is much lower than the figures provided by police departments in Redding and Davis, cities that are different demographically, but share commonalities, too.

In Redding, a city 70 miles to the north with a smaller, generally more conservative population, the police department reported 34 hate crimes during the 2016-2018 period. The police department in Davis, a liberal university town 98 miles to the south with a much smaller population, reported 29 hate crimes during that period.

Nationwide, hate crimes against individuals soared upward in 2018, according to a recent FBI report. The report shows the overall number of hate crimes dipping a tiny amount, but a spike in hate-driven murders. It shows increases in crimes targeting Latinos, transgender and gender non-conforming people.

More than half of hate crime victims nationwide are probably not reporting incidents to police, according to a story by ProPublica, the investigative news agency that spearheaded Documenting Hate, a project that ends this year.

There’s another obstacle to accurate tracking — inconsistent counting by police. Civil rights groups say police often do a poor job investigating and tracking hate-driven violence — a view that, locally, many share.

“Nobody feels comfortable going to the police,” said Chico State sociology professor Lesa Johnson. “Students and people of color are victims of crime quite often, but have had enough experience with police to know that their complaints won’t be taken seriously.”

ChicoSol was unable to reach Chico PD for comment on this story, despite repeated efforts by phone and email over a three-week period.

Earlier this year, Chico Police Deputy Chief Matt Madden said his department takes all incidents seriously. “We want everybody to feel safe,” Madden told me after the June 2 graffiti spree that left southwest Chico marred by swastikas and racist language. “We have a diverse community, and don’t take this lightly.”

For the past several years, African Americans in Chico have been holding “Freedom Schools” – named after the Freedom Schools set up for black communities in the 1960s — that facilitate telephone networking and use of a mutual support system. It provides a sort of neighborhood watch involving both students and longtime community members who try to keep each other safe and reduce dependence on and need for law enforcement.

A growing gulf with police

The FBI defines a hate crime as a criminal offense driven by bias against a victim’s race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity or disability. People who are targeted because of their nationality, under California law, are also hate crime victims.

Police hate crime reporting is voluntary; most groups agree the FBI produces, at best, a “vast undercount,” ProPublica reports. Some police departments don’t report at all, and more than 80 percent report zero hate crimes in their jurisdictions. The University Police Department (UPD) reported zeros for 2016-2018.

On a personal note, I remember the sickening feeling I had when I thought that my Latino family members had been targeted. On a morning back in 2008, I found our car had been spray painted with the words “white power.” I wondered if the perpetrator was a neighbor and if I should worry about our safety. As a white woman, it felt easy and logical to report the incident to police, which I did. So when I began reporting for ChicoSol on these kinds of incidents, I was startled by the isolation of many victims.

Minority students who had come to Chico State and found themselves in a town that is 82 percent white feared drawing more attention to themselves by talking to a reporter. Yet, they had stories to tell, and in the telling, one sensed a longing to be heard. One group said they had rocks thrown at them in the presence of a police officer about the time of the 2016 presidential election.

They feared they might not be taken seriously if they reported these incidents – like that of the rock-throwing — and that, even worse, they might be treated as suspects instead of victims. Their mistrust was rooted in personal experience in other cities, but in this city as well.

Johnson said three young women recently went to Chico police to report a case of cyberstalking. The cyberstalking had recently escalated and become frightening. The problem itself had nothing to do with race, but the victims were women of color.

An officer, Johnson said, told the women to document the communication in case something happened. “They felt like police didn’t listen to them,” she said. “They [the officers] didn’t write anything down and looked very disinterested.”

As I interviewed community leaders for this story, though, they brought up something else that continues to cloud the relationship between Chico PD and people of color — the March 2017 police shooting that killed Desmond Phillips, a young black man in mental crisis. That killing created a “gulf,” Johnson noted.

“The death of Desmond Phillips really did rock both students and community members who are people of color,” she said.

Because the killing was ruled justifiable by the district attorney’s office, said Vince Haynie, an African American pastor, some officers are “a little more arrogant now.”

“I wish the chief would have said, ‘You officers were wrong. We should have backed off and called mental health people in,’” Haynie said.

“If they shoot me,” Haynie added, “nobody’s going to be prosecuted. That’s the system – there’s a lot of Jim Crow stuff going on in the law enforcement community.”

Haynie said people of color are “suspects out the gate” and therefore reluctant to call police.

The Phillips killing was the first of seven fatal shootings that involved Butte County law enforcement agencies from 2017 to January 2019, but it was the tragedy that became emblematic of the community’s view of Chico PD, says George Gold, a member of Concerned Citizens for Justice, a group that is calling for a greater emphasis on de-escalation tactics and community policing.

2019: A year of unsolved hate crimes

The majority of submissions to the Documenting Hate database from this area, in the beginning, reflected racist speech and racial profiling that sometimes appeared inadvertent and sometimes designed to hurt. But this year, the submissions had a different and more alarming tone. They were related to some of the multiple incidents of racist graffiti in Chico’s public spaces, and in one case, an assault.

Early this year, an international student was bicycling to class at Chico State when he was struck by someone on the street and told to “go back” to where he had come from, according to a database submission verified in interviews with faculty members. The student was threatened with a knife, and some passersby shooed the attacker away. Police were called, and officers conducted a “welfare check” on the student later in the day.

But here’s what you won’t find in a police report or hate statistic: The student was so “distraught” he was “contemplating quitting the [college] program,” according to the database submission.

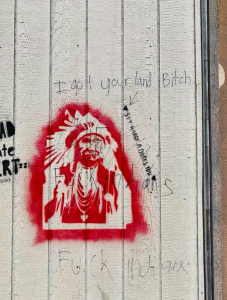

In April, racist, homophobic and sexist graffiti was used to deface faculty bulletin boards in Chico State’s Butte Hall. In May, a vandal or vandals defaced a Mechoopda mural on West Second Street, writing the words, “I got your land bitch,” and drawing swastikas. On June 2, Chico residents awoke to a particularly ugly scene: That of graffiti on at least 10 sites in the southwest section of town that included swastikas, the wording “white power” and the N-word.

As Chicoans were discovering the graffiti on storefronts and walls, more anti-Native graffiti appeared about the same time, said Ali Meders-Knight, a member of the Mechoopda Indian Tribe-Chico Rancheria who has been working with other artists on the mural. A stenciled picture of an American Indian appeared on a downtown wall, again with the wording, “I got your land.” None of these cases have been solved.

Meders-Knight reported the mural vandalism to police, but said she was never contacted again about the matter. She also told me that her tribe has endured multiple incidents of vandalism and has reported cases to police for insurance purposes.

“It’s a matter of protocol rather than protection,” she said. “The police don’t feel it’s a threat. We haven’t seen a lot of cooperation. We don’t expect anything to come out of [reporting] it.”

Ten days after that June 2 downtown graffiti spree, CPD said it had a suspect in custody, Thomas David Bona, who was arrested after allegedly yelling racist epithets at a local motorist and vandalizing the man’s car.

Bona was never charged, though, in connection with the June 2 spree — in spite of a Butte County District Attorney’s press release that bore the confusing headline, “Charges Announced in Chico Vandalism Spree.” Charges filed against Bona are related to other incidents; District Attorney Mike Ramsey said there wasn’t sufficient evidence to charge him with the spree.

(Bona has been charged with a hate crime in connection with his reported confrontation with the motorist, a hate crime allegation in connection with racist graffiti that appeared in April on a Valero gas station, and in connection with other incidents of vandalism and graffiti in April and early May. Court proceedings were suspended in October so that Bona can be treated for mental illness, Ramsey said.)

Ramsey says his office pressed hate-related charges in seven cases over three years — from 2016 to the end of 2018 — but that figure only represents prosecutions. Hate crimes are especially complex to prosecute, one of many reasons why police tracking is essential.

Chico PD: an open door that’s tough to get through

I contacted the CPD’s Deputy Chief Madden on Nov. 18 to ask about the June graffiti investigation. Madden promised to research the matter and get back to me quickly. I heard nothing, but during the next weeks I requested an interview with Chief Mike O’Brien; I wanted to ask about the protocol for hate-crime tracking, whether the 2019 incidents would be included as hate crimes in next year’s report.

His office asked me to submit questions in writing, which I did. I still heard nothing back.

O’Brien was a guest speaker at the Dec. 7 Butte County NAACP banquet in Oroville, where he remarked that we are in “challenging times.” The chief said he has an open-door policy, a willingness to engage in “tough conversations,” and a commitment to community policing.

I asked him that evening about the pending interview request, and he promised a quick response. It hadn’t arrived at the time of this story’s posting.

At Chico State, UPD’s Sgt. Dale Glander responded promptly when I called, though he was surprised by my question. Would the graffiti in Butte Hall be reported as a hate crime to the FBI? “If that meets the criteria of what the FBI is looking for, it should be on there,” he said.

Hate crime neglect

ProPublica says there’s been a “widespread lack of training for frontline officers,” generally speaking, to equip them to investigate and track hate crime.

That may be why police departments in the North State differ greatly in how much emphasis they give to hate crime; it likely depends on department leadership, community expectations and resources. Davis Police Department — it counted 29 hate crimes compared to Chico PD’s four during the past three years — has an entire Web page devoted to hate crime.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is calling for legislation that would encourage police to do a better job tracking hate crime with funding incentives. The Commission recommends officer training to identify hate crimes and improved community outreach to encourage victims to report.

About one year ago, I met with a group of students who shared personal experiences with hate, described their frustrations with authorities, and then insisted, in the interest of safety, that I not include the material in a story. This year, I met with faculty members who, concerned about their own well-being and that of their students, spoke on condition of anonymity.

A window was cracked open, and the greater community glimpsed what happens in times that challenge, that isolate and intimidate, when victims aren’t so sure that the system works for them.

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol and a freelance journalist.

Excellent story which reflects deep knowledge of the history of this issue. And ZERO hate crimes in Chico this year? Highly unlikely.

Chief O’Brien reports ZERO hate crimes, rubbish. Remember the ChicoSol article of December 2017, exposing the two owners of the local indoor shooting range, both are Chico Police Department officers, unapologetically mocking the Black Lives Matter movement with a “Black Friday Matters” billboard promotion. The comments of the two CPD officers, who are quoted in the article, are revealing and should be troublesome to the good people of Chico.

Statistics are constantly manipulated by government career politicians. When I was at the Sheriffs office a large percentage of crimes went without reports. Some were because the reporting party gave up due to time lapse and were not available. Many were sluffed off. Felonies were listed as MS (miscellaneous service) calls without a case number. Without a case number these crimes are not reported to the FBI uniform crime reporting. So for the Sheriff this translates into bragging rights for reducing crime and what a great job he is doing. The hate crime issue is the same. We live in a hate crime free County by not reporting hate crimes. All is well and our career politicians are protecting and serving. Remember The Front Page? Make some high profile arrests and report low crime before the election and get reelected.

So no police killings in almost a year? What changed?

Chico and Butte County dont like the stink of hate crimes in our fair well managed community. So they just fade from the statistical reporting to avoid the truth.

It is the same stink that Chico avoids with the Chico Chinese Massacre. Chico is my home town but how many Chico residents know about it? 6 Chinese laborers shot in a cabin and 4 killed.14 March 1877. Hate crimes are not new. When they are ignored for political benefit this just creates more violence as it did in 1877 Chico.

Earlier this year, Chico Police Deputy Chief Matt Madden said his department takes all incidents seriously. “We want everybody to feel safe,” Madden told me after the June 2 graffiti spree that left southwest Chico marred by swastikas and racist language. “We have a diverse community, and don’t take this lightly.” Quote from a recent ChicoSol article.

This comment is highly suspect, to say the least. The outgoing CPD chief has anointed this officer to replace him. The good people of Chico deserve the unvarnished truth from the top cop in their city.

There’s a reason this area is called “Calibama.” We are a multiracial couple and lived in Chico for several years, after 40 years of activism in Southern California. We were shocked, naively, I guess, by Chico’s whiteness and weird attitudes. I think we were surveilled after joining some local advocacy groups. I was approached by a strange woman who tried desperately to be my “friend” and interrogated me about my views on police and activism. Our advocacy group was infiltrated by a guy who had served time in Susanville and whose wife was about to be indicted for real estate fraud. When a friend of ours ran for city council, the police chief was caught sending around a memo saying he (the candidate) hung out with “cop haters.”

I saw police beat up a white kid for calling them “popo.” The young, poor, white population of the region is in terrible shape, economically, educationally, etc., and that may give rise to some of the white nationalism among them.

Mexicans and blacks were definitely not represented among the population and I doubt if they’d be welcome. Cal State Chico appeared to be one of the worst universities I’ve ever encountered (I’m a professor of English) despite the president making an absurd salary of $400,000. The cops constantly picked up kids for MIP and DIP (Minor in Possession of Alcohol) and Drunk in Public–I could find few cultural or intellectual activities on campus, but drinking was rampant on and off it. I know all about the Chinese massacre referenced in another comment; local tribes were enslaved and mistreated as well.

That Afro-American man who claims he was pelted by beer cans has to do more than have his girlfriend state that “she saw the bruises”. No fact based information mentioned, including contacting local law enforcement.

No credibility on this fake news!