As California assesses the lasting impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, public health experts say they are concerned about managing future health emergencies after battling a disinformation crisis.

For the last two years, county public health departments have been tasked to respond to a pandemic unlike anything seen in decades. As guidance from the California Public Health Department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for managing local crises shifted weekly, local departments like Butte County’s faced an enormous task of keeping the public informed using rapidly changing methods, including Facebook and YouTube – with mixed results.

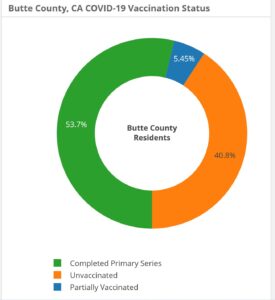

Social media played a crucial part in informing the public, but communication and health experts think it also may have contributed to the crisis. As of this month, only 54% of the county’s residents have had two COVID-19 vaccine doses and nearly 41% are unvaccinated, while statewide 76% are vaccinated and 17% are unvaccinated.

In Butte County, only 17.7% of children ages 5-11 and 39% ages 12-17 are fully vaccinated. This compares poorly to the statewide averages of 36% and 67%. (See sidebar on vaccinating children.)

Public health officers become targets

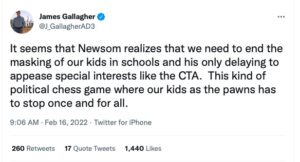

While Butte and counties around the state used social media to release videos and updates about the pandemic, some political leaders used the platforms to attack state mandates. Rep. James Gallagher attacked Gov. Gavin Newsom on Twitter, particularly when the state enforced shutdowns during new waves and high hospitalizations. Gallagher encouraged re-opening businesses and schools even in violation of a state-mandated shutdown.

The county relied heavily upon the public health officer for new information about the pandemic each week. As the person who runs Butte County Public Health and has the power to issue health orders, implement state regulations and evaluate county health programs, Dr. Andy Miller became a key figurehead for communicating new, verified medical information – sometimes daily – as the coronavirus emergency grew.

Spokesperson Lisa Almaguer said to meet the challenge, the department used social media posts from the state and CDC, and communicated directly with schools, gyms and restaurants. Public health staff established a call center, conducted weekly press conferences and posted informational videos with Miller, who played a high-profile role in efforts to inform and educate communities. The office designed a COVID-19 dashboard for the public to keep up on cases, hospitalizations and deaths that it updated on weekdays.

But within several months, some residents grew impatient to “reopen” the county and reverse the state’s restrictions. Miller, who had been outspoken about enforcing state Department of Public Health standards, resigned in July 2020 amid a second viral wave. He was soon replaced by Dr. Bob Bernstein, who would resign in September 2021.

According to Almaguer, the department took months to find a replacement in Dr. David Canton of Merced County. After several months as interim officer, Canton was hired as full-time health officer on April 29 this year.

During this time, Butte County Public Health faced an ongoing barrage of pushback from people on social media. The department faced continued backlash while trying to communicate how to save lives by wearing masks and getting vaccinated, as did many around the country. Almaguer would not comment on whether these factors had any connection to the department’s difficulty in keeping a public health officer. The Butte County resignations took place during a wave of such resignations all over the country.

Social media backlash

One Public Health post in August 2021, showing outcomes of COVID for those vaccinated versus those non-vaccinated, drew more than 250 comments. As people commented with theories they found on unverified websites about the virus, the public health department sometimes interacted with people to correct the information or answer direct questions.

In another social media post in December 2020, the department discussed the importance of following expert guidance and science; that post received more than 300 comments that in some cases slammed public health for imposing restrictions on businesses and other county operations.

Many people also spoke out on these posts to support the department, thanking them for standing up for science against protests and what some called “bullying” in the comment threads.

Almaguer said the office “ramped up” educational efforts about vaccines, masking and overall prevention, and tried to respond to false information. She said the department was “very limited” in its ability to delete comments from its social media accounts.

“We have to allow for the exchange of information, even if inaccurate,” Almaguer said. She added there were also comments that countered misinformation, which she believes were “self regulating” the misinformation.

Canton said when he began as interim health officer, he was “certainly concerned” about local vaccine resistance, because “the vaccination had been shown to be effective at decreasing moderate to severe disease, as well as hospitalization and death.”

Asked about the struggle over the Covid narrative, he said, “We certainly support people’s right to free speech and their opinion.”

“Our job as the health department is to put out credible, reliable sources of information and make sure people have the information that’s accurate and timely,” he added. “A lot of times the information people cite is either misquoted, misstated or misinterpreted. If we can put out information that is accurate, timely, credible and scientifically sound … in the end people will see that and understand what the right thing to do is.”

He said limited resources determined what the department was able to accomplish with messaging people about the virus in a rural area.

“We’ve learned that we want to have as many different ways to reach as many different people and populations as possible,” he said. “We don’t want anybody to be left behind in Butte County because they didn’t get the message.”

Miller, after retiring from the county in 2020, now works at Enloe Medical Center. While he did not respond to requests for comment, the hospital’s communication team said the medical center worked closely with Butte County Public Health throughout the pandemic.

“Early in the pandemic there were many unknowns, which naturally made the public nervous and scared,” the medical center wrote in an email. “We started posting on social media to offer accurate information and counter misinformation. We wanted to offer insight to help foster confidence and help people feel better.”

The communication team said tactics like posting FAQs and answering common questions about COVID-19 and vaccines, as well as commissioning many educational videos and daily updates, were key to this effort. Enloe and Public Health were assisted by nonprofits and civic groups like Northern Valley Catholic Social Services and the Hispanic Resource Council to increase Spanish language content and reach more members of the community.

But other community members said they were disappointed in the county’s overall efforts to communicate accurate information, and were concerned that misinformation still spread on networks that both Public Health and Enloe managed.

Story-telling as a vehicle

Ashley-Michelle Papon, the project coordinator in outreach and development for the nonprofit Migrant Clinicians Network that works with migrant and mobile populations, said that misinformation has heavily impacted marginalized populations like immigrants and undocumented people. The Network received a grant from CDC to work with people within the Latino community to explore their experiences with and attitudes and beliefs about COVID, as these communities were disproportionately affected by COVID.

“They disproportionately make up the workforce of frontline workers and are often tasked with working in unsafe conditions such as migrant farm work, warehouse employees or food service,” Papon said. She added Latino residents face less access to accurate information from public health agencies and often have less trust in those agencies due to historic and present discrimination.

Photographer Robin Hayes is working with the Network to train workshop participants in production of a photo series that will document personal stories. The photo stories will be submitted to the CDC for use in a cross-cultural public information campaign. She said participants have told her constantly changing pandemic information often “felt contradictory,” and they didn’t know what to believe.

“I also heard some people say that if they did go for help, if they spoke Spanish, they faced racism at the doctor’s office. They didn’t get the care they needed until they had someone else advocate for them.

“I understand how knowledge about this virus and what to do about it changes as we go,” said Hayes, who herself has a background in public health. “But the normal population might not understand that.”

Constantly shifting medical information can be confusing to people, who may be especially vulnerable to misinformation and theories spread online, she added.

Papon said that while social media has been indispensable to modern society, she thinks it has also been “a unique proliferator of misinformation.”

“COVID was the first real phenomenon where we have disregarded all medical convention … to erode facts in favor of opinions that have no basis,” she said.

She said the Trump administration helped contribute to an atmosphere of fear and incredulity – the former president often attacked the pandemic’s lead medical expert Dr. Fauci and used Twitter to spread dissent about the virus – which she said spread into the medical profession, despite many doctors’ hard work to contain it.

“The most horrific thing to see is that it’s so rampant, that even the folks who are supposed to be the gatekeepers … have swallowed the proverbial Kool-Aid,” Papon said. “A lot of the early rhetoric that came out was that the only people who have anything to fear are the people who are already sick.”

Papon is unhappy that public health departments generally do not remove misinformation from their social media accounts when it appears in comment threads.

“I am so appalled that we think it’s all right to tolerate misinformation, because the folks who are capable of having discussions with the right information will balance it out,” she said.

“People often don’t trust doctors until the stakes are high enough.”

Papon added that she thinks political leaders contributed to the spread of dangerous misinformation as they focused on campaign donors, and that has affected, in particular, marginalized populations.

“It goes back to that concept of acceptable loss,” she said. “It’s OK to put these individuals up like lambs for the slaughter, because they aren’t the groups who political leaders tend to count on to get them elected.”

“It is no longer simply about public health guidance” — Dr. Stan Salinas

Jacqueline Camacho, a Chico resident who is a participant in the Network photography workshop, said members of her family – relatives in both Chico and in her hometown in the Mexican state of Jalisco — were sick with COVID early in the pandemic. Some were only slightly ill or asymptomatic, but in Mexico her father was so sick he required specialized treatment.

When the vaccine became available, Camacho and her family heard many of the rumors that were circulating, including that the illness was a “plot of the government to reduce the world’s overpopulation,” she told ChicoSol, speaking in Spanish. “It was very dramatic.”

But all members of her immediate family were persuaded to get the vaccine after receiving well-documented information from “Promotores,” a program run by Northern Valley Catholic Social Services. Camacho estimates that less than 50 percent of the people she knows in her Latino community circle are vaccinated.

Camacho is optimistic about the usefulness of the Network workshop. “I think it will help create more awareness, to inform everyone about COVID,” she said.

Cases soar with misinformation

Other counties have said they don’t delete posts from comment threads, either. Marin County Public Health, which reports one of the highest vaccination rates in the state at above 90%, like Butte, has a total semi-rural population of less than 300,000.

Spokesperson Laine Hendricks said the department sought legal counsel and was told that comments are protected under First Amendment rights. The team increased communication efforts using videos and PSAs, and said while social media can be useful, the average person “must be more vigilant to do their research and decipher what is factual and what is bonk.”

“Our response to those things was to ignore them as it was clear people were upset and venting,” she said. “Or if we did respond, try to do so in a positive way and with empathy.”

Like Butte, Marin also faced problems on its public pages. But Hendricks said for every six commenters sharing misinformation on a post, there were usually three times more “people commenting with factual information or calling those trolls out for spreading fear.”

The New York Times Covid tracker today shows a 4% increase in the case rate in Butte County during the past two weeks, while the case rate for Marin County dropped 25%.

Stan Salinas, chair of Chico State’s Public Health and Health Services Administration, said misinformation in fact has an impact.

“People exposed to online misinformation related to COVID or COVID vaccines are certainly more vaccine hesitant,” he said.

“Because of the politicization of COVID, people are especially entrenched in their beliefs,” he added. “It is no longer simply about public health guidance because in order for some people to accept this guidance they would need to abandon their political beliefs, and that’s a steep hill to climb.”

Salinas said people’s identities are increasingly defined by their political beliefs, and trusted messengers like family, community and faith leaders have more success reaching people.

“For some people who are very entrenched, especially in right-wing politics, getting a vaccine or wearing a mask is no longer just about doing what is best for your personal health and the health of your community, it’s an abandonment of their identity,” he said.

Salinas added he thinks the problem will worsen the chances of managing future public health crises.

“Our political leaders have learned that politicizing issues like this polarizes the electorate, and our information sources which thrive on engagement benefit from promoting misinformation,” Salinas said.

Natalie Hanson is a contributing writer to ChicoSol. Leslie Layton contributed reporting to this story. This story was published with support from an Ethnic Media Services fellowship.

Another excellent article. Thanks! Well researched and well written.

I wish the AMA had taken a more active role in communication about the virus, and the local newspaper. Way in to it they started posting info about numbers of people in hospital and deaths, but seemed late the the game. Hope someone is developing a communications protocol for the next wave or next virus.

Thank you Natalie Hansen and ChicoSol for this timely article.

Another outstanding article by Natalie Hanson. Thanks to Chico Sol for giving her opportunities to do in-depth reporting about our area, even though she is now in the Bay Area.